30 years after Chernobyl disaster, an arch rises to seal melted reactor

Enter the Chernobyl zone, and you might expect the worst: Security guards at a checkpoint 19 miles away from the site of the world’s worst nuclear accident scan departing vehicles for signs of radiation, as wolfish strays linger around the checkpoint.

But pass the derelict villages and collective farms evacuated after the disaster 30 years ago this month, and a new skyline emerges over the ill-fated nuclear plant.

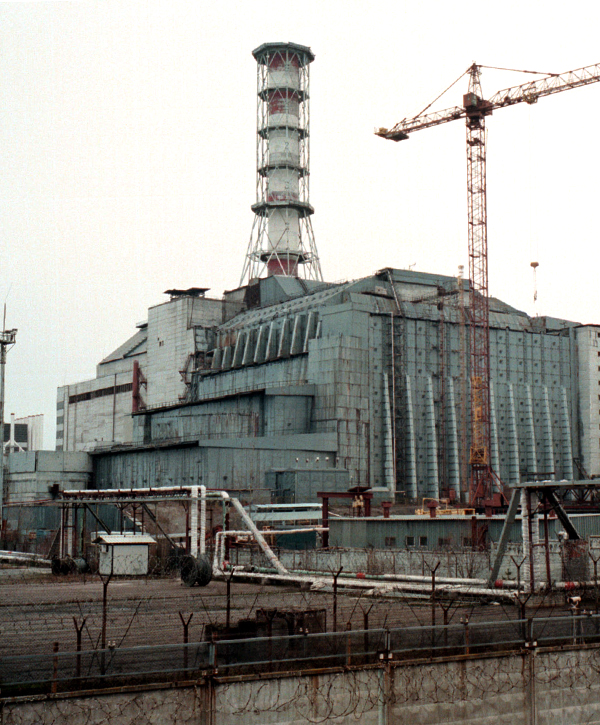

A workforce of around 2,500 people is finishing a massive steel enclosure that will cover Chernobyl’s reactor 4, where the radioactive innards of the nuclear plant are encased in a concrete sarcophagus hastily built after the disaster. The zone is now aglow with the reflective safety vests of construction workers.

If all goes to plan, the new structure—an arch more than 350 feet high and 500 feet long—will be slid into place late next year over the damaged reactor and its nuclear fuel, creating a leak-tight barrier designed to contain radioactive substances for at least the next 100 years.

The project, known as the New Safe Confinement, is a feat of engineering. It will take two or three days to slide the 36,000-ton structure into place. The arch, which looks something like a dirigible hangar, is large enough to cover a dozen football fields.

“You could put Wembley Stadium underneath here, with all the car parks,” said David Driscoll, the chief safety officer for the French consortium running the construction site.

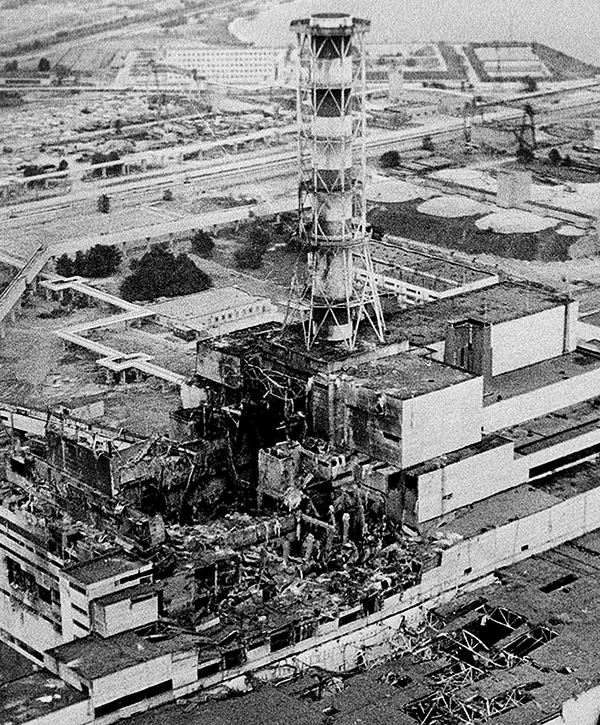

Three decades ago, an army of workers scrambled to build a concrete sarcophagus around Chernobyl Reactor 4, which released a radioactive plume after a reactor fire and explosion on April 26, 1986.

At least 30 people died as an immediate result of the accident, which contaminated parts of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia and sent radioactive dust and debris over Europe. Pripyat, the company town of 50,000, was completely evacuated.

An aerial view of the Chernobyl nucler power plant, the site of the world’s worst nuclear accident, is seen in April 1986, made two to three days after the explosion in Chernobyl, Ukraine. In front of the chimney is the destroyed 4th reactor. (AP Photo)

The NSC is the largest man-made moving object on land ever built and is designed to last for a hundred years. The NSC is 108 meters tall, 162 meters long, and 257 meters across its base. CREDIT: John Wendle for The Wall Street Journal

CHERNOBYL

Emergency workers and evacuees received doses of radiation significantly above natural background levels, according to the World Health Organization. Researchers acknowledge high levels of thyroid cancer among people who were children at the time of the accident, from exposure to radioactive iodine.

An exclusion zone remains around the Chernobyl plant, keeping it off limits to all but authorized workers, most of whom live in a town just outside the zone.

Today, working at heights, not exposure to radiation, is the main safety concern here, Mr. Driscoll said.

Workers on scaffolding or tethered to ropes are installing the layers of steel and insulation that are supposed to keep heat and moisture out—and radiation in. The steady construction is a contrast to the rushed emergency work back in 1986.

“It was like mobilization for war,” said Lev Bocharov, one of the lead engineers at the time. “Everyone ran. The slower you ran, the bigger the dose you received.”

Building the sarcophagus took seven months. Mr. Bocharov on four occasions was lowered into the blasted reactor inside a lead bathyscaphe-like tank with a window 12 inches thick to survey the damage. The concrete shelter was designed to last at least 30 years, Mr. Bocharov said.

“It was done as solidly as possible,” he said. “But the task was not to seal it hermetically.”

Today, the workforce is monitored closely for exposure to radiation. Nicolas Caille, project director for Novarka, the consortium of Vinci SA and Bouygues SA, the French contractors running the project, said about 1,000 people work on a typical shift at the construction site, keeping to a schedule of 15 days in and 15 out.

The €2.15 billion ($2.45 billion) shelter implementation plan has been funded by international donors and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, a nonprofit lending institution. But the Chernobyl cleanup faces a shortfall: €100 million is needed to finish a storage facility for highly radioactive spent nuclear fuel from the other three Chernobyl reactors, all now offline

The EBRD’s spent-fuel-facility contract is with a U.S.-based energy technology firm. When the dollar-denominated contract was signed, the euro was stronger against the dollar; with the two currencies approaching parity, the bank faces a shortfall.

“This has dug a huge euro hole,” said Vince Novak, the director of the nuclear-safety department for the EBRD. “Our income is in euros.”

Mr. Novak said donors would meet later in April to discuss financing to finish the project, which is financed separately from the Chernobyl shelter fund.

Currently, spent fuel rods are stored in an aging facility. Completion of the project, Mr. Novak added, “has always been somehow in the shadow of the New Safe Confinement because it is not as attractive, not as sexy.”

“But in terms of importance for nuclear safety, it’s equally important,” he said.

Even if donors plug the gap, Chernobyl will continue to pose a financial challenge for Ukraine. More than 40 countries and the European Bank for International Development have contributed to the Chernobyl containment work, and international donors say it will be years before the Kiev government can take on the larger share of the burden. Ukraine is battling Russian-backed separatists in the eastern Donbas region, sending the economy reeling.

383381 01: A general view of the sarcophagus that covers the Ukraine»s Chernobyl nuclear power plant»s fourth reactor November 16, 2000 destroyed as a result of the April 26,1986 explosion. The Chernobyl plant, the site of the world»s worst nuclear disaster, was closed down for good December 15, 2000. (Photo by Yuri Kozyrev/Newsmakers)

“As you know Ukraine right now is in a very difficult financial situation” because of the war, said Igor Gramotkin, general director of the Chernobyl plant. “But I am confident the economy of Ukraine will recover and will be able to support all of the project activities.”

As the arch nears completion, the forest is now encroaching on Pripyat. The nuclear ghost town is a favorite of photographers: The place was evacuated in a hurry, sometimes with plates set on the table, and Pripyat remains frozen in time like an atomic-era Pompeii.

Hanna Vronska, Ukraine’s acting minister of ecology and natural resources, said the Ukrainian government was considering the creation of a biosphere to preserve the unique ecosystem for further study.

Wildlife has flourished in the forest, which is largely off limits to humans. Officials say species such as lynx, wild boar, wolves, elk, bear and European bison have rebounded.

“It will be possible to do scientific research in the area as well as to preserve the unique ecosystem of the region,” Ms. Vronska said. “The biggest threat to nature is not the radiation, but humans.”

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом