The shifting sea routes of Europe’s refugee crisis, in charts and maps

Twice in the past two weeks, dozens, if not hundreds, of people have drowned in the Mediterranean Sea — but in both those cases, not one of them was Syrian. For the past year, the world has been largely focused on the rafts filled with refugees from Syria's civil war that have traveled incessantly from Turkey to the nearby Greek island of Lesbos. But 600 miles to the west, a long-used route between Libya and Italy is drawing attention again after a spate of tragedies.

It is easy to assume that the news from Libya and Italy is a reflection of new dynamics stemming from an agreement between the European Union and Turkey that came into effect last month, aimed at effectively shutting down the migrant route to Greece. Under the terms of the deal, almost all those who reach Greece's shores will be returned to Turkey. NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg told reporters in Turkey that "international coordination," including the E.U.-Turkey deal, has brought numbers on this route "significantly down."

But Barbara Molinario, a spokeswoman for the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Italy, told my colleague Sudarsan Raghavan last week that "the question is whether there has been a switch in routes because of the Turkey-E.U. deal, and so far the answer is no."

And though Italy reported a surge of arrivals in March, numbers in April decreased compared with last year.

So who are the people crossing from Libya to Italy?

Prior to last summer, Italy was at the center of the Mediterranean refugee crisis. Through 2014, many of the arrivals there were indeed Syrians. Tens of thousands used the "Central Mediterranean route," landing mostly in Sicily. But those numbers, as shown in the chart below, decreased precipitously as smugglers began to favor the "Eastern Mediterranean route," which involves a far shorter sea journey and eliminates the need to traverse Libya, which is partly controlled by the Islamic State militant group and otherwise mired in political instability. It is also simply a shorter and less complicated route overall; Turkey borders Syria, and the Turkish coast is less than 10 miles from numerous Greek islands.

Between the start of 2015 and recent months, arrivals in Greece far outpaced those in Italy. More than a million landed in Greece, compared with less than 200,000 in Italy. Both routes see increases through the summer months, when travel over land, often on foot, is easier to endure for refugees.

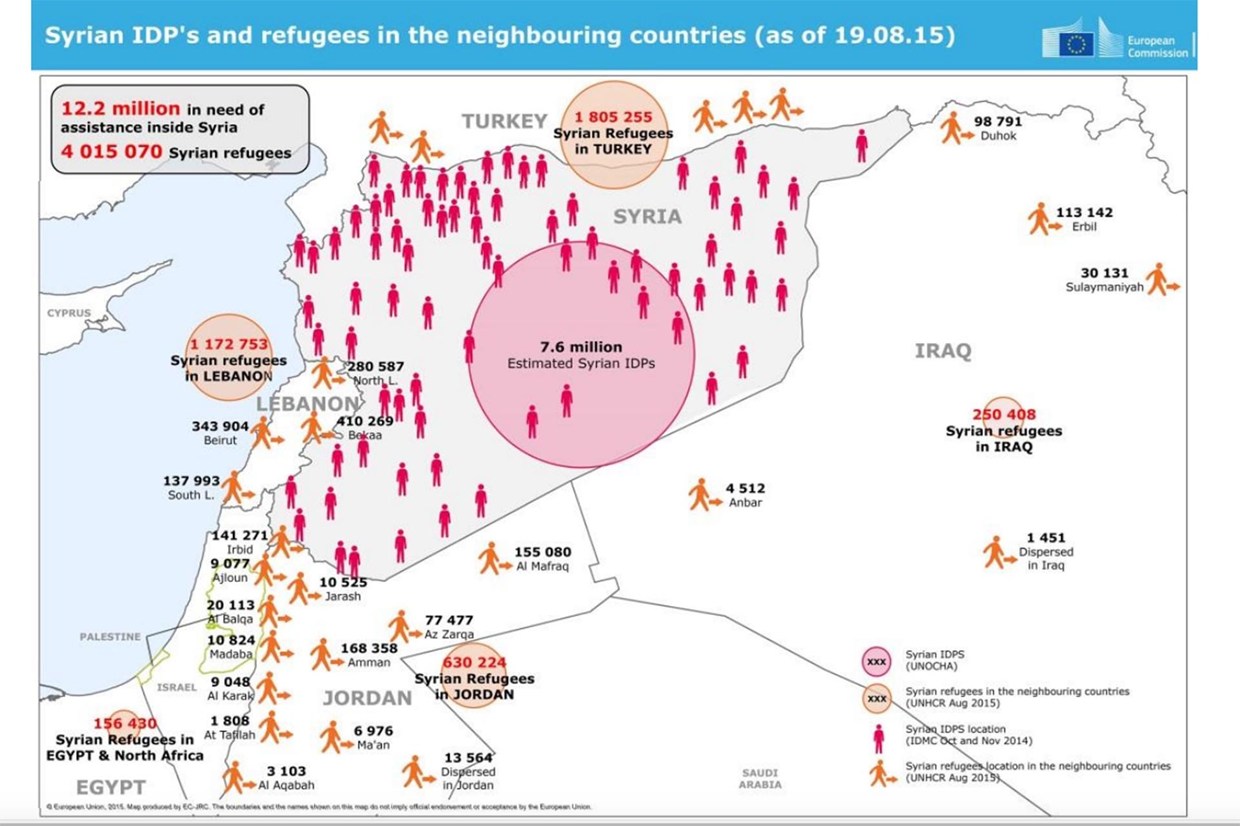

Arrivals in Greece are mostly fueled by war and its aftermath in Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq. Ninety percent of arrivals in Greece come from the world's top 10 refugee-producing countries. And 40 percent of arrivals are children, which is an indication that many of those using this route are families.

The death toll on this route so far in 2016 is 376.

The route to Italy draws mostly from Africa. The nationalities are more varied, as are the reasons for seeking a new life in Europe. Eritreans make up a full quarter of arrivals in Italy. Many are fleeing a brutal dictatorship that conscripts all of their country's young men and is accused of forcing many of them into hard labor. Others are leaving regions that are plagued by terrorism, such as Nigeria and Somalia. And a sizable chunk are trying to escape the grinding poverty, unemployment and political crises that persist in nations such as Senegal, Ivory Coast and Morocco. Only 15 percent of arrivals in Italy come from the world's top 10 refugee-producing nations, and three-quarters of arrivals in Italy this year are men.

The death toll on this route is more than double the toll for the Eastern route. This is largely because of the comparative length of the journey, though some analysts have said that the quality of boats used is also inferior.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом