The world’s most beautiful schools

They are buildings in which to teach and learn – but they can be magnificent too. Jonathan Glancey discusses some of the most stunning seats of learning.

Nancie Atwell, American winner of the inaugural Global Teacher Prize, was in London in early November where she put across her simple, resonant message: children are increasingly in danger of “being tested rather than taught”.

A classroom, says Atwell, who was chosen for the Global Teacher Award from over 5,000 nominations from 127 countries, should be a place of “wisdom and happiness” rather than stress and fear of failure.

Atwell’s words would have been music to enlightened educators down the centuries, especially those who added ‘beauty’ to Atwell’s “wisdom and happiness".

Stowe in Buckinghamshire is, without doubt, one of the world’s most beautiful schools. It was founded in 1923 in the Arcadian landscape of one of England’s most romantic country estates threatened with demolition at the time. Saved, after a spirited fight led by the architect Clough William-Ellis, it was turned into a school. John Fergusson Roxburgh, Stowe’s founding headmaster, said it would be a school where every pupil would “know beauty when he sees it all his life.”

A2EFNJ South Front of Stowe School Buckinghamshire England UK. Image shot 2006. Exact date unknown.

His pupils were enveloped in beauty every day, from landscaped gardens by Capability Brown studded with enchanting follies to classical buildings by a pantheon of great 18th Century English architects, among them John Vanbrugh, William Kent, Robert Adam and John Soane. Since 1989, the gardens have been in the care of the National Trust while thoughtful new buildings – like the girls’ dormitories by Rick Mather Architects – have added quietly to Stowe’s lustre.

Lagoon of learning

Not every school can be Stowe, an English public school and a place of privilege, and yet beauty can be found in the least privileged settings, too. Which school could be more special than the floating school in Makoko, a waterborne shanty town off the coast of Lagos. Here, NLE architects, a Dutch firm led by Nigerian-born Kunlé Adeyemi, have shaped a simple, yet hauntingly beautiful timber school floating among lagoon houses.

Makoko is a poor place, although like Stowe 90 years ago it has been threatened with destruction by politicians and officials who see it as an illegal settlement. Now, with a school that has won admirers worldwide, Makoko is a source of pride for an increasing number of Nigerians. Working closely with local people, NLE have brought not just education to Makoko’s children, but self-esteem and a new beauty to this shanty town, too.

Beauty was both essential as well as natural to the founders of early seats of learning, especially those where spiritual and academic learning were seen as one as the same thing. The beauty as well as the practicality of the medieval colleges of Oxford and Cambridge, for example, have not just been celebrated and proven over many centuries, they have also inspired the design of university campuses worldwide.

Shelf love

Certain undergraduates choose a college like Magdalen, Oxford as much for its beauty – its medieval cloister and tower designed by William Orchard and its later Palladian and Victorian additions set by the River Isis back onto a timeless deer park – as for its scholastic virtues. It is perhaps not a coincidence that Magdalen’s library houses a fine collection of books on architecture, including its first, a 1649 Dutch edition of Vitruvius’s De Architectura, a treatise dating from the 1st Century BC. Vitruvius reminds architects of their duty to build with firmness, commodity and delight.

C22RME Nice image of Magdelen College in Oxford

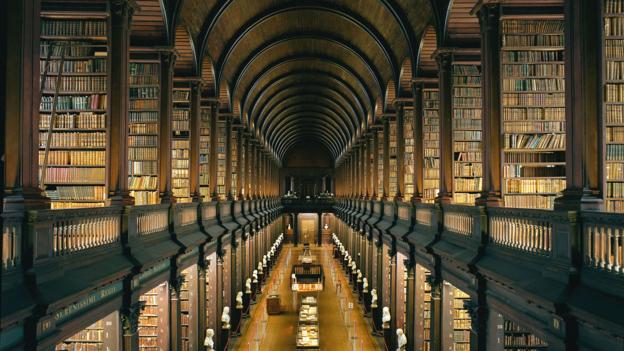

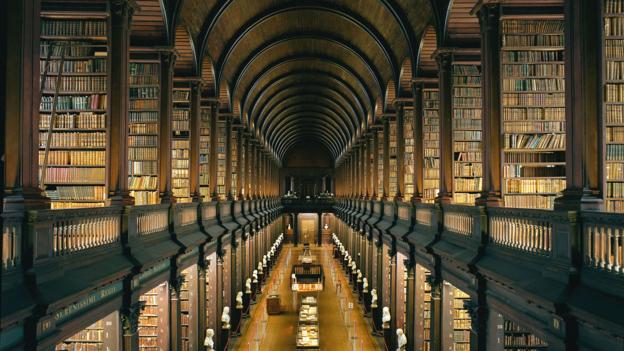

The most delightful places of learning have always been lined with books. To wander into the Long Room of the Old Library of Trinity College, Dublin is to experience a literary and architectural epiphany. The 213-ft (65m) long room is timber-lined throughout, rising – since 1860 – to a great barrel vault crowning alcoves of leather-bound books set between busts of prominent philosophers and literary giants.

When completed in 1732 to designs by Colonel Thomas Burgh, a military engineer, architect and MP, the library was both one of the largest and most determinedly civilised new buildings in this city of vivid literary, lyrical architectural and intense academic endeavour.

CN75HD Library at Trinity College, Dublin — The Long Room

Cloisters and courtyards

Whether Gothic or Classical, or in styles of North Africa, the Middle East and the Silk Route, colleges adopted the architecture of cloisters and courtyards. These offered, as they still do, a sense of calm, quiet and introspection, necessary to writing, research and book learning.

One of the most exquisite campuses in the United States is that of Scripps College, a liberal women’s college founded in 1926 by 89-year-old Ellen Browning Scripps in Claremont, a small town of ‘trees and PhDs’, 35 miles (56 km) east of Los Angeles. Its Spanish Colonial or ‘Mission’ style architecture is serene and perfectly suited to both the Californian climate and to the college’s setting below the San Gabriel Mountains. Here, spaces like the cloistered Eucalyptus Court of Balch Hall designed by the LA architects Sumner Hunt and Silas R Burns engender a sense of Nancie Atwell’s “wisdom and happiness”. They are also beautiful.

While Magdalen, Trinity and Scripps colleges are special places founded by and endowed with financial largesse, and although they are complemented by schools and universities built in more recent years as diverse as Lev Rudnev’s soaring Moscow State University (1953) or the gentle, yet gravity defying loops of Lausanne’s Rolex Learning Centre (2010) by the Japanese architects Sanaa, beauty can be conjured at low cost and in any setting, urban or rural.

C8GX47 Lausanne, university, Switzerland, Europe, canton, Vaud, Rolex, Learning centre, building, construction, building, architecture,

New generation

Immediately after World War Two, England’s Hertfordshire County Council began a programme of rapid school building. Lightweight steel structures designed and refined by local authority architects – notably Stirrat Johnson-Marshall and David and Mary Medd – offered bright, airy, spacious classrooms and other spaces realised on a scale that ensured the wellbeing of pupils and teachers alike. Some featured sculptures by Henry Moore. This was enlightened, altruistic design at a time when Britain was all but bankrupt.

Today, some architects are trying to imbue something of this altruistic spirit in a new generation of British city schools. The brand new, low-cost Hackney New School in East London by Henley Halebrown Rorrison squeezes into an inner-city site cheek-by-jowl with former industrial buildings. It cannot offer the spaciousness of a post-war Hertfordshire school or the classical beauty of Stowe, yet it makes maximum use of space inside – doing away with relentless corridors – and is a calm riposte to the many schools and academies of recent decades that have been too like factories or office blocks for comfort.

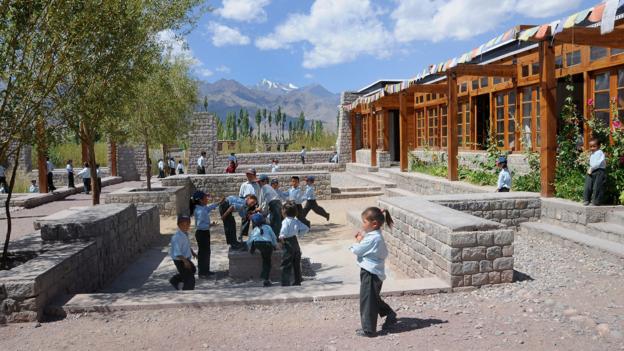

BE63PA Elementary school children in the modern playground of the private-religious Druk White Lotus School, Shey, Ladakh, India

Equally enlightened, if very different indeed, is the beautiful Druk White Lotus School at Shey, high in the mountainous regions of Ladakh, India. Designed by Arup Associates and Ove Arup and Partners, this has been under construction for the past 15 years, growing to accommodate children from mountainous villages as money, climate and fierce weather allow. Aimed at bringing the latest education to Himalayan children while nurturing their Tibetan Buddhist culture, the school is proving to be a seat of wisdom, happiness and beauty. It is not cost, but imagination that counts the most in the design of schools and colleges, this and the idea that they are, above all, places to learn and to grow.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом