The piano gets a radical

The pianist Gergely Bogányi realised his instrument had no equal to the Stradivarius violin – so he attempted to build one. Is it the perfect piano? Clemency Burton-Hill reports.

It wasn’t like I woke up one day thinking: today I’m going to build a new piano for the world,” says Gergely Bogányi, the Hungarian concert pianist and, of late, piano designer. “But I’ve always been a bit of a revolutionary. For a long time I had been thinking: this is just not good enough; let’s build something better.”

He is speaking to me from his factory outside Budapest, “in a beautiful area, next to the Danube and close to the forest”, to tell me more about the Bogányi piano, the radical new instrument that he finally presented to the world earlier this year after a “very long spiritual and musical journey”.

Even the greatest concert halls don’t always have the most refined and well-adjusted pianos – Gergely Bogányi

For generations, the world’s greatest pianists have played the same instruments, with all their glories and faults left unchecked. But Bogányi is not the kind of person to leave nagging questions unanswered: “Like most pianists, I played many bad instruments throughout my childhood. But my great surprise [as a professional pianist] was discovering that even the greatest concert halls don’t always have the most refined and well-adjusted pianos. I always felt something was missing for the modern world, for modern pianism and expression.”

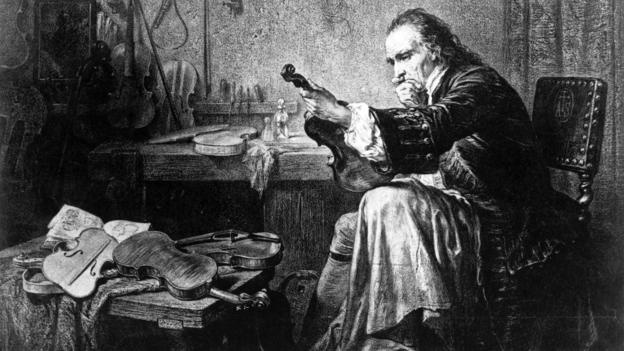

Antonio Stradivari or Stradivaius (c.1644 — 1737) the Italian violin maker of Cremona, circa 1700. Original Artwork: From a painting by Hamman Original Publication: People Disc — HL0215 (Photo by Rischgitz/Getty Images)

His revolutionary dream – “which seemed so absolutely impossible it was all the more inspiring” – was to combine form and function in an entirely new way. After years of development, he and his team have finally realised it in the form of an instrument that is breathtaking to behold, but which ultimately “serves the music”. The results are potentially game-changing. “My aim was [to serve] the noble tradition of the piano sound at the same time as being genuinely innovative,” he says. “Of course, I respect and adore older pianos, but we are in 2015. I think it is time for us to search for a new truth.”

When I ask if he has found it, he immediately replies: “Absolutely!” But then just as quickly concedes that, by his very nature as someone who is “always searching for better and better”, the process will never stop. “We are not saying, OK, here is perfection,” he says, “but rather: here is the piano in another dimension, with another approach. And as a result another sound, a more desirable sound, has been born.”

Sound advice

With a few exceptions, classical instrument-making has not traditionally adhered to the doctrine of constantly evolving progress: the piano has remained essentially unchanged in its fundamental design for 200 years. The prototype for the perfect violin is even older: nobody has yet bettered the form created by Antonio Stradivari, who was born in 1644.

Bogányi 's 2015 piano is certainly an extraordinary-looking thing, but its radical nature goes far beyond visual aesthetics. “Right from the beginning, I told my designer that I’d like something elegant and noble, but with nothing that merely made it look good without serving the instrument,” he explains. “It is a very complex shape because it’s not only a beautiful design but needs to serve several purposes at the same time: it needs to carry the double function of being traditional but very, very innovative and modern; it needs to carry a flow of the music; and it needs to be spiritually inspiring.”

I ask him to explain the chief difference between his and more traditional pianos and he answers without missing a beat. “The sound. As a musician, as a pianist, that of course had to be my main focus. The piano is a percussive instrument and our biggest problem is always how to make it sing and how to sustain that singing. So I wanted to combine the warm and friendly, almost human sound of a 19th Century piano such as Érard, with the power of what is needed for today’s modern concert halls. If you look at a graph, normally you would see the percussive attack at the beginning of the note, then it dies out. I didn’t want to hear this hammer hit but the sound itself, singing on.” Employing a combination of "the most refined traditional wood you can find in the world today" with a composite carbon fibre that is the "highest in high-tech spaceship technology" he and his team developed a new soundboard and sound system. They also hit upon the unlikely idea that the left leg of the piano could work “as a sound-directing element, directing the sound towards the audience.”

Everyone knew that the construction of the older pianos was not good enough – Gergely Bogányi

Astonishingly, his designer had no previous experience working with pianos. But this was deliberate. “My team are geniuses,” Bogányi enthuses. “Yes, the designer had never designed a piano, the chief engineer had never engineered one, the technician had not worked on anything like this before. But this meant they could all approach the project with an open mind. They were brave, and I was always encouraging them to take risks and find solutions that would not usually be ‘allowed’ in the sanctified world of piano-making; this idea that 'it’s holy, you can’t touch it, it’s perfect'. In the classical industry, everyone knew that the construction of the older pianos was not good enough, but it was not something anyone dared to bring up. But we were brave enough to ask some questions – why this; why that; why not? Why has there been no major development of the piano for centuries?”

Hungarian pianist and creator Gergely Boganyi plays on a new piano during a presentation for the press at the Budapest Music Center on January 20, 2015. The fundamental difference of the Bogányi Piano to a traditional piano is the sound-board made of multi-layered carbon-fibre with a rippled surface that is sprung and detached from the piano frame. The new material makes the piano resistant to exterior conditions like heat or humidity and prevents the soundboard from breakage. AFP PHOTO / ATTILA KISBENEDEK (Photo credit should read ATTILA KISBENEDEK/AFP/Getty Images)

With his project taking years and costing an undisclosed amount, does he ever regret asking those questions? He laughs. “Thank God I never understood in the beginning that it would be almost impossible to do!” But he is evidently delighted by the response: having launched the piano this spring he is now fielding interest from all over the world. The Bogányi piano – which takes a team of up to 100 people six months to build and can be fully customised for the individual – is now officially on the market, although production is likely to remain small-scale for at least the near future. Does he ever imagine a day when his name will be synonymous with the instrument in the manner of, say, Steinway? “Until now, my team have just been working and working, solving problems and dreaming and not thinking so much about what it was going to be like when other people tried it. Of course it was very surprising and wonderful that almost everybody has been so enthusiastic, and of course, I would be very happy if our piano would find its place and fulfil its mission to breathe a new air to music, and concert halls and individual pianists, but…” He breaks off, laughs again, a note of incredulity in his voice. “Well, who knows. We weren’t planning it, but it seems to be a little earthquake that we have started…”

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом