The most audacious scam in history

How do you make someone bend to your will? In an extract from her new book on con artists, Maria Konnikova finds answers by exploring the psychological tricks of one of history’s most shocking fraudsters.

In October 1822, Gregor MacGregor, a native of Glengyle, Scotland, made a striking announcement. He was, he said, not only a local banker’s son, but the Cazique, or prince, of the land of Poyais along Honduras’s Black River.

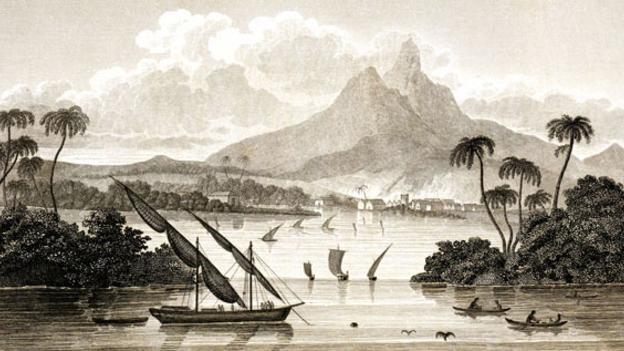

A little larger than Wales, the country was so fertile it could yield three maize harvests a year. The water, so pure and refreshing it could quench any thirst – and as if that weren’t enough, chunks of gold lined the riverbeds. The trees overflowed with fruit, and the forest teemed with game. Painting an exotic, Edenic vision of a new life abroad, his proposal offered quite the contrast with the rainy darkness and rocky soils of Scotland.

"The water of Poyais, he said, was so pure it could quench any thirst – and as if that weren’t enough, chunks of gold lined the riverbeds"

What Poyais lacked, he said, was willing investors and settlers to develop and leverage its resources to the fullest. At the time, investments in Central and South America were gaining in popularity, and Poyais appeared to be a particularly appealing proposition.

Scotland didn’t have any colonies of her own, after all. Could this not be a corner of the new world for her own use?

Would you have fallen for the scam? MacGregor was a master salesman – and when you consider the psychological underpinnings behind con artistry, it is little wonder that many people were indeed fooled.

Con artists have long recognised that persuasion must appeal to two very particular aspects of human motivation – the drive that will get people to do something, and the inertia that prevents them from wanting to do it. In 2003, two social psychologists, Eric Knowles at the University of Arkansas and Jay Linn at Widener University, formalised this idea by naming two types of persuasive tactics.

The first, alpha, was far more frequent: increasing the appeal of something. The second, omega, decreased the resistance surrounding something. In the one, you do what you can to make your proposition, whatever it may be, more attractive. You rev up the backstory – why this is such a wonderful opportunity, why you are the perfect person to do it, how much everyone will gain, and the like. In the other, you make a request or offer seem so easy as to be a no-brainer – why wouldn’t I do this? What do I have to lose?

Psychologists call it the ‘approach-avoidance’ model of persuasion

They called the juxtaposition the approach-avoidance model of persuasion: you can convince me of something by making me want to approach it and decreasing any reasons I might have to avoid it. According to Columbia University psychologist Tory Higgins, people are usually more likely to be swayed by one or other of the two motivational lines: some people are promotion-focused (they think of possible positive gains), and some, prevention-focused (they focus on losses and avoiding mistakes).

An approach that unites the alpha with the omega appeals to both mindsets, however, giving it universal appeal – and it is easy to see how MacGregor’s proposition offered this potent combination.

He published interviews in national papers, for instance, touting the perks that would come from investing or settling in Poyais. He highlighted the bravery and fortitude that such a gesture would demonstrate: you wouldn’t just be smart; you would be a real man. The Scottish Highlanders were known for their hardiness and adventurous spirit, he wrote; Poyais would be the ultimate testing ground, a challenge and gift, all in one. He pointed those who needed more convincing to a book on the virtues of the small island nation, by the elusive Thomas Strangeways (actually MacGregor himself). His prospectuses enticed the public with their masterful promises, their lure of opportunity, their appeal to scarcity, their admonitions not to let this perfect moment pass by.

MacGregor used the six principles of persuasion instinctively

Alone, this powerful mix of alpha and omega can already start to explain the allure of MacGregor’s idea – but his fine-tuned approach also incorporates further tactics that must have multiplied its attractiveness. Psychologist Robert Cialdini, one of the leading experts on persuasion, argues that six principles govern most persuasive relationships: reciprocity (I rub your back, you rub mine), consistency (I believe the same thing today as I did yesterday), social validation (doing this will make me belong), friendship or liking (exactly what it sounds like), scarcity (quick! there isn’t much to go around), and authority (you seem like you know what you’re talking about).

Consider how many of those MacGregor used instinctively. Reciprocity: you invest with me, and I give you the opportunity of a lifetime – a life so wonderful that no one else can give you something comparable. Social validation: you will be the most Scottish of Scotsmen, the most respected of people, a pioneer and role model. Scarcity: act now, for this is not an opening that will remain. If Scotland doesn’t sweep Poyais up, someone else will – and there goes the nation’s one chance at colonial greatness. Authority: Dr. Strangeways surely knows that of which he speaks. If you don’t trust me, then at least trust him – though why wouldn’t you trust me? After all, I’ve published in the best media of the time.

When the settlers arrived, they found the reality to be a stark departure from the brochures: a wasteland

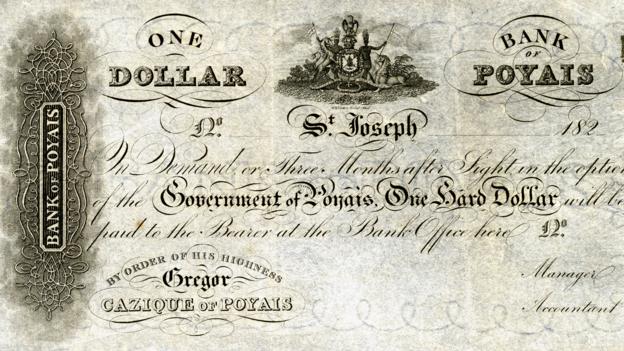

The tactics worked precisely as anticipated. They were beyond successful. Not only did MacGregor raise £200,000 directly – the bond market value over his life ran to £1.3 million, or about £3.6 billion today – but he convinced seven ships’ worth of eager settlers to make their way across the Atlantic. In September 1822 and January 1823, the first two, the Honduras Packet and the Kennersley Castle, left for the mythical land, carrying some 250 passengers. The mood was high; MacGregor’s salesmanship had been unparalleled. But when the settlers arrived just under two months later, they found the reality to be a stark departure from the allure of MacGregor’s brochures. No ports, no developments, no nothing. It was a wasteland.

For Poyais had never existed. It was a figment of MacGregor’s fertile mind. He had drawn his investors and colonisers to a desolate part of Honduras – and soon, the hardy Scotsmen began dying. The remaining settlers – only one third would survive – were rescued by a passing ship and taken to Belize. The British Navy recalled the remaining five ships before they reached their destination. MacGregor escaped to France.

If he was at all remorseful, he had a strange way of showing it: not long after his arrival he started the Poyais pitch all over again. His initial investment may have evaporated, but his mastery of the art of persuasion was undiminished. In a matter of months, he had a new group of settlers and investors ready to go. France, though, was a bit more stringent than England in its passport requirements: when the government saw a flood of applications to a country no one had heard of, a commission was set to investigate the matter. MacGregor was thrown in jail. After a brief return to Edinburgh, he was forced to flee once more, pursued by the wrath of the original Poyais bondholders. He died in 1845, in Caracas. To this day, the land that was Poyais remains a desolate and undeveloped wilderness—a testament to the power of the rope in able hands.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом