Black German woman learns a shocking family secret: Her grandfather was a Nazi

Atlanta, Jennifer Teege thought she knew the hard truths of her life: that her German mother left her in the care of nuns when she was 4 weeks old, and that her biological father was Nigerian, making her the only black child in her Munich neighborhood.

But the hardest truth came to her years later on a warm August day in Hamburg when she walked into the central library and picked up a red book with a black-and-white picture of a woman on the cover. It was titled "I Have to Love My Father, Don't I?"

As Teege, then 38, flipped through the pages, she felt she'd been caught in a furious storm that had suddenly come from nowhere.

She had unearthed the ghastly family secret.

She looked at the names of people and places in the book and realized that the woman on the cover was her biological mother.

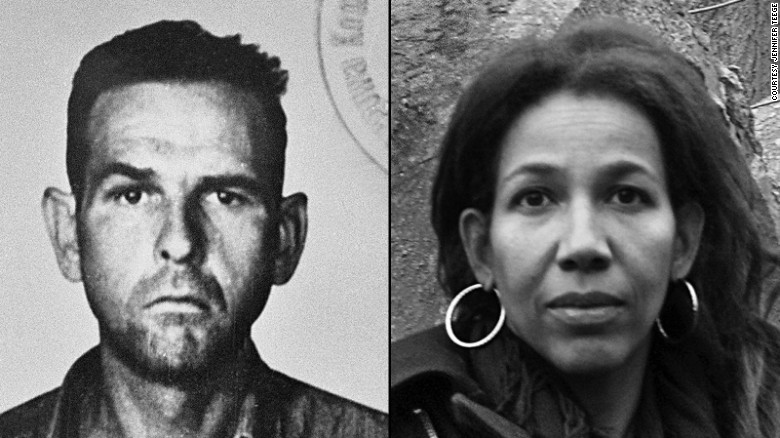

And the father in the title was none other than Amon Goeth, the sadistic Nazi who was commandant of the Plaszow concentration camp in Poland. Many came to know about Amon Goeth through Ralph Fiennes' portrayal of him in the 1993 movie "Schindler's List."

Teege doesn't know why she was drawn to the book. But on that day, Teege learned that she — a black German woman who'd gone to college in Israel and befriended the descendants of Holocaust survivors, who now had a successful career and a loving family — was the granddaughter of a monster.

It was a moment that cut her life in two. There was the "before," when she knew nothing of her family's sinister past, and "after," when she was forced to live with that truth.

In the library, Teege grew cold knowing she was connected by blood to a man responsible for the deaths of 8,000 Jews. She checked out her mother's book, lay down on a bench outside and called her husband to come fetch her.

Teege had battled depression all her life and had wondered what was behind her sadness. In fact, she'd gone to the library that day for psychological research.

"I always had this inner feeling that something was wrong," she says, likening it to being inside a house with many locked doors. "I didn't know what was behind them."

She looked in the mirror at herself, saw Amon Goeth's chin, the same lines between the nose and mouth, and thought: "Do I carry something of him in me?"

After the initial jolt eased, she embarked on a quest to know everything. Eventually, she wrote a book of her own: "My Grandfather Would Have Shot Me: A Black Woman Discovers her Family's Nazi Past."

She feels fairly certain that her grandfather would not have hesitated to kill her. She is, after all, far from the Aryan ideal espoused by Amon Goeth, who, according to Teege's book, went to the gallows saying, "Heil Hitler."

"It's a story you can't take to your grave. It's exceptional," Teege says on a recent January day at Atlanta's Emory University, where she spoke about her identity and her journey to reconcile with it.

She has left her job in advertising and made her personal history her life's work now. She speaks about how she progressed from her initial fear and guilt to acceptance of her history and knowledge that she is a very different person than her grandfather.

"Today, I am not afraid of him," she says. "We are two very different people."

And she talks about how, for a long time before her discovery, she didn't believe in fate, only in chance. But now she thinks differently. She thinks about the choices she made that took her to Israel and led her to her mother's book. She believes she made them for a reason.

Some things in life, she says, are predetermined.

Living with the dead

Teege's case was exceptional, thought Peter Bruendl, a Munich psychoanalyst who has treated her and other grandchildren of Nazis.

Teege first had to deal with being a mixed-race child given up for adoption and the feelings that can bring, of being unwanted and worthless, Bruendl says in Teege's book. And then, when she thought she was settled in life, she suffered again with the discovery of her family history.

"Frau Teege's experience is heartbreaking," he says. "Even her conception was a provocation."

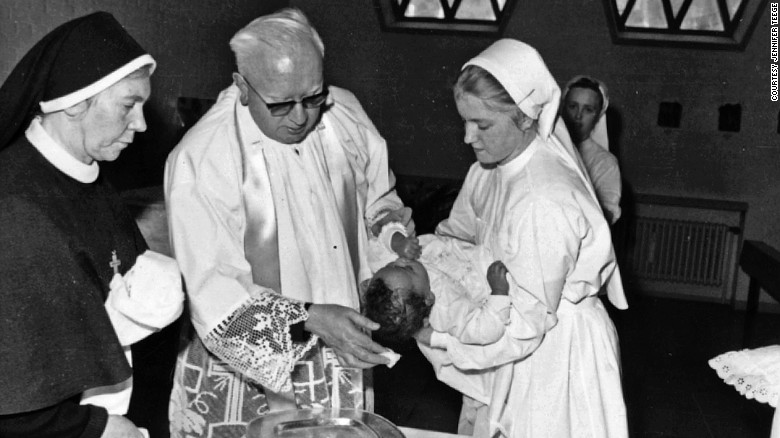

Teege's mother became pregnant after a brief affair with a Nigerian student. She was working six days a week and battling depression and took the baby to Salberg House, a Catholic home for infants in suburban Munich.

For the first few years of Teege's life, her mother occasionally came to see her at Salberg House and sometimes took the child to visit her grandmother. A foster family took Teege in when she was 3 and adopted her four years later, insisting that her mother refrain from further contact.

Teege wouldn't see her mother again until she was 21, after a younger half sister called and re-established contact. Born Monika Goeth, Teege's mother had since taken her husband's last name and is now known as Monika Hertwig.

Hertwig had never told her young daughter about their Nazi blood. Nor did she mention it at that meeting.

"She decided not to say anything," Teege says. "She thought that if I didn't know, it would be easier for me. I believe her."

Teege found the book at the library 17 years later.

Just hours after she took the book home on that day in 2008, German television aired a PBS documentary called "Inheritance" in which the filmmaker had taken Teege's mother and Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig, a Jewish maid subjected to Amon Goeth's cruelty, back to Plaszow.

Teege, however, did not see the film until later; even then, she could not finish it in one sitting. Beyond the shocking history, it was too much to bear to see intimate details about the mother who'd been absent in her life.

In retrospect, Teege thinks her mother should not have agreed to be filmed in such a vulnerable state. She looked so lost and lonely.

"My mother was fragile then. She wasn't ready to be on screen," Teege says.

The film documents awkward moments in which Hertwig is still repeating phrases she heard growing up, that Amon Goeth only shot Jews because they spread infectious diseases.

"Monika, please, stop. Stop right now," Jonas-Rosenzweig tells her as the two are standing in Goeth's villa at Plaszow.

At the time, Hertwig was still piecing together the story of her father's horrors.

No one in post-war Germany spoke of what they knew of the Holocaust. Nobody wanted to talk about what happened to the Jews, Hertwig once said. "They were extinct like the dinosaurs."

Hertwig's mother — Ruth Irene Kalder, Goeth's mistress at his villa in Plaszow — beat her when she asked too many questions. The older woman had always spoken of Goeth as a "war hero," and Hertwig grew up surrounded by lies, thinking of her father as another victim of the Third Reich.

Hertwig finally learned from her grandmother that Goeth was far from a hero, that he tortured and killed people.

Ruth, who later in life took Goeth's surname, never showed any remorse except once, according to Hertwig. Shortly before Ruth committed suicide in 1983, she said she should have done more to help people.

After finding Hertwig's book, Teege knew she had to seek her mother out — not so much for a reckoning, she says, but because she had too many questions swirling in her head. She wanted details that only her birth mother could know.

By then, many months had passed and Teege had already gone to Poland, already seen the places where her mother had also returned to learn the truth. She found Hertwig's address and went to see her, not knowing whether there would be acceptance or rejection. She had learned so much about her mother through her book, the documentary and online research. Yet she didn't know her.

They visited Ruth's grave together, and Hertwig talked about Amon Goeth as though he were at Plaszow only yesterday. Hertwig has said in interviews that speaking ill of her father feels like a betrayal of her mother.

She was living with the dead, Hertwig told her daughter.

Teege says she saw in her mother what she has seen in relatives of other Nazi perpetrators, especially their children. Many cannot bear to live with the sins of their fathers. Others have sterilized themselves, as though a Nazi gene could be passed on through birth.

Teege is thankful she is different than her mother, who Teege says still lives every day with the notion that she has to atone for Goeth's deeds. Teege has seen this kind of suffering in the children of Holocaust victims as well.

"The second generation had a lot of trouble dealing with the Holocaust," Teege says. "My generation, we are different. We know the difference between responsibility and guilt."

Teege doesn't believe in inherited guilt. Everyone, she says, has the right to his or her own life story.

Destiny

Teege's life story is punctuated with ironies and coincidences so great that they prompted her to rethink the concept of fate.

As a young woman, long before her discovery, she attended the Sorbonne in Paris for a year and, in a life drawing class, she met Noa, an Israeli woman. Teege later vacationed in Israel, and on one trip, after sleeping through her 4:30 a.m. alarm and missing her flight back to Germany, she ended up staying. She attended Tel Aviv University, earned a degree in Middle Eastern and African studies and learned to speak Hebrew.

"That I chose Israel … that I missed the flight and stayed — this makes my story more striking," Teege says. "Destiny."

Today, I am not afraid of him. We are two very different people.

Jennifer Teege

She was in Israel when "Schindler's List" opened, and everyone was talking about Steven Spielberg's Holocaust movie. Teege watched it later on TV in her Tel Aviv flat. It was just a movie to her then, one that she thought had too much of a Hollywood ending.

The subtitle of her mother's book was, "The Life Story of Monika Goeth, Daughter of the Concentration Camp Commandant in 'Schindler's List.' " That day in the Hamburg library, Teege's mind churned to recall the movie. Suddenly, it became deeply personal.

Teege says she does not want to keep secrets from her friends and family. Two years went by before she could reveal her Nazi roots to her friends in Israel, descendants of Holocaust victims and survivors. She didn't know if any of them were directly connected to Plaszow, and she was afraid how they might react.

But in her book, Teege describes her Jewish friends as being empathetic. "They cried with me."

She also has spoken with her young sons.

"It was important to me not to keep it a secret," she says. She doesn't want them to go through the shock of discovery, which became almost as traumatic for Teege as the truth itself.

"But I have not let them watch 'Schindler's List,' " she says. "They should be older."

People assume she has watched the movie many times. They are wrong. She doesn't feel the need to watch it over and over. She knows her grandfather's story.

A woman with two lives

It has been more than seven years since Teege learned she was the granddaughter of Amon Goeth. She thinks of her stranger-than-fiction life as a puzzle with many pieces but missing a frame. Her discovery at the Hamburg library helped her put it all together.

"My life is much better than what it used to be," she says.

She is thankful she had an identity in her "before" years. That's what she held onto in the "after" years.

Teege's mother has not called her daughter again since their last meeting. In Teege's book, Hertwig says she didn't understand her daughter's need for reconciliation and felt it was too late to start a relationship.

But Teege's quest to know her true identity opened other doors. Growing up, she'd never felt a need to find her biological father. But once she had come to terms with her mother's family, she sought out her father, too. They finally met, and the two remain in contact.

"It's a nice addition — to know my black heritage," she says. "And crucial. It's part of my identity."

At 45, Teege says she is now a woman with two lives. She is a mother and a teacher. That's the part she calls normal. The other life is led as the granddaughter of Amon Goeth. She knows she has to keep the two separate.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом