Obama: Beauty pressures have ‘always been harder’ on black women

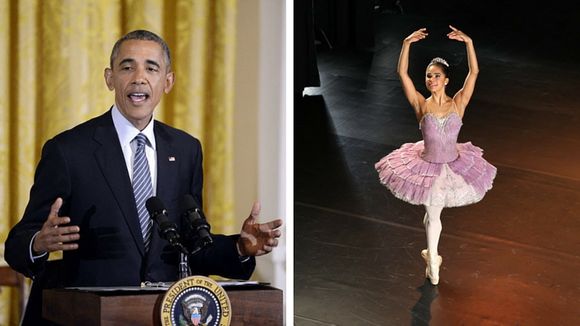

Last month, President Barack Obama and ballerina Misty Copeland sat down with TIME to discuss their rise in their respective fields, the country’s persisting racial discord and the grassroots movements looking to radically change the racial climate.

Among the many highlights from TIME's transcript of that dialogue? Obama’s efforts to help his daughters foster positive body image, particularly in a society that judges black women more harshly.

"When I was a kid I didn’t realize as much, or maybe it was even a part of which is the enormous pressure that young women are placed under in terms of looking a certain way. And being cute in a certain way," Obama explained. "Are you wearing the right clothes? And is your hair done the right way? And that pressure, I think, is historically always been harder on African American women than just about any other women. But it’s part and parcel of a broader way in which we socialize and press women to constantly doubt themselves or define themselves in terms of a certain appearance. And so Michelle and I are always guarding against that. And the fact that they’ve got a tall gorgeous mom who has some curves, and that their father appreciates, I think is helpful."

Obama maintained that it’s still an ongoing battle, however. "I mean Malia (will) talk about black girl’s hair and will have much opinions of that. And she’s pretty opinionated about the fact that it costs a lot, it takes a long time, that sometimes girls can be just as tough on each other about how they’re supposed to look. And so it’s, as a parent, that’s a constant learning process that you’re trying to hold the fort. And that’s why somebody like Misty ends up being so important."

In essence, representation matters. But, as the pair discussed, there is still a systemic pattern of coded language and behaviors that work to actively preclude black women from certain pursuits.

After Obama mentioned how her body type was characterized as too "athletic" or "large" for ballet, Copeland, the first female African American principal in the American Ballet Theatre’s history, explained how subtle sentiments like that are used as excuses for exclusion.

“You know, my experience has been that a lot of what I’ve experienced has not always been to my face, or it’s been very subtle. But it’s in a way that I know what’s going on and I feel it deep inside of me,” she said before adding that those pressures only deepened her commitment to her craft. "It’s also allowed me to have this fire inside of me that I don’t know if I would have or have had if I weren’t in this field."

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом