Paris attacks: Hollande drops plans to strip nationality

French President Francois Hollande has dropped plans to change the constitution to strip militants convicted of terror attacks of their French nationality.

"A compromise appears out of reach," Mr Hollande said after the two houses of parliament failed to agree the reforms.

The proposal followed November's Paris attacks which killed 130 people.

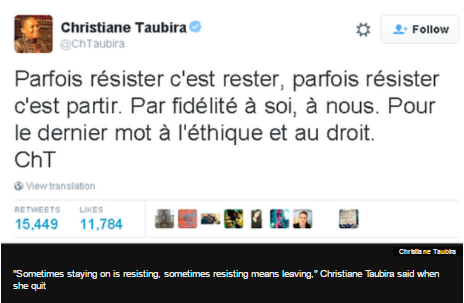

But it ran into huge opposition and led to Justice Minister Christiane Taubira resigning in February.

"I noticed that parts of the opposition have been hostile to any revision of the constitution," Mr Hollande said after a cabinet meeting.

"I deplore this attitude, because we have to do anything we can under these serious circumstances."

But former president and leader of the opposition party, The Republicans, Nicolas Sarkozy, said Mr Hollande's leadership was at fault.

"By promising everything and the opposite of everything, in reality he condemns the country to stalemate and immobility," he said.

Meanwhile a suspect in a failed French attack plot has been charged with membership of a terrorist group, French media reports.

Reda Kriket, 34, was arrested last week and found to have rifles and explosives in his home.

Two-tier system

France's president outlined the changes in the aftermath of the gun and bomb attacks by Islamist militants who targeted a concert hall, a major stadium, restaurants and bars on 13 November 2015.

A step too far for Hollande: Lucy Williamson, BBC News, Paris

It is a brave leader who sets out to change France's constitution. The nation likes to date much of its identity from the revolution that created it.

Changing it would be achievement enough for a president in the flush of a political honeymoon. For President Hollande and his deeply divided Socialist Party, it has proved a step too far.

Mr Hollande's tough response to the November attacks brought him a brief uptick in approval. He and his prime minister have been pushing back against the left-wing of his party, in a bid to show he can deliver leadership and change.

With fractures running through both the Socialist Party and the centre-right opposition, and many French voters complaining of stasis at the heart of their political establishment, this is one defeat he could do without.

Aside from a plan to strip dual-nationality citizens of their French nationality if convicted of terrorist offences, Mr Hollande also wanted emergency powers to be given a new status under the constitution. This has also been abandoned.

Sole French nationals had been excluded from the proposal. Stripping them would have made them stateless citizens — which is not permitted under international law.

Critics said the bill would have a discriminatory effect, creating a two-tier system of French citizenship.

Some of the fiercest opposition came from within Mr Hollande's Socialist Party, although it found favour among France's right-wing.

The Socialist-dominated lower house removed the reference to dual nationality when it approved the bill, meaning the punishment could in principle be applied to all nationals, although in practice French nationals with sole citizenship were unlikely to be affected.

But the opposition-controlled upper house, the Senate, restored the original wording.

Constitutional changes in France need the approval of three-fifths of the combined houses of parliament and both need to agree on the exact terms of the changes.

Frederic Dabi from pollster Ifop warned the move would "revive the perception of a president who is not determined, who lacks authority, whose hand is shaking".

France has been under a state of emergency since 14 November. It is currently due to expire on 26 May.

The right to a nationality is enshrined under Article 15 of UN Declaration on Human Rights, which sought to establish universal standards across the globe.

The article adds "no-one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his nationality nor denied the right to change his nationality".

Despite this, the UN refugee agency estimates there are at least 10 million stateless people around the world from various factors including discrimination, the emergence of new states or legal disputes.

Stateless individuals lack the same basic rights as ordinary citizens, such as access to the job market, state health care and education, or the ability to buy property or open a bank account.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом