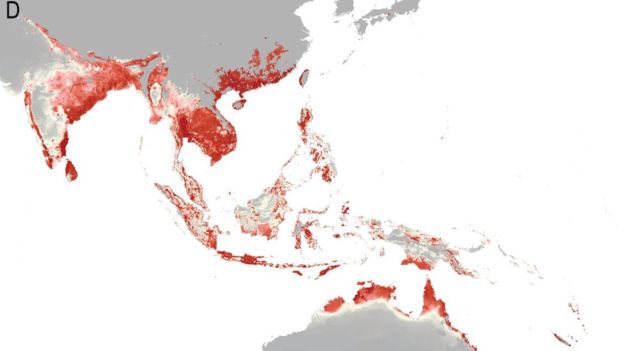

Zika virus: 2.2 billion people in ‘at risk’ areas

More than two billion people live in parts of the world where the Zika virus can spread, detailed maps published in the journal eLife show.

The Zika virus, which is spread by Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, triggered a global health emergency this year.

Last week the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention confirmed that the virus causes severe birth defects.

The latest research showed mapping Zika was more complex than simply defining where the mosquito can survive.

One of the researchers, Dr Oliver Brady from the University of Oxford: "These are the first maps to come out that really use the data we have for Zika — earlier maps were based on Zika being like dengue or chikungunya.

"We are the first to add the very precise geographic and environmental conditions data we have on Zika."

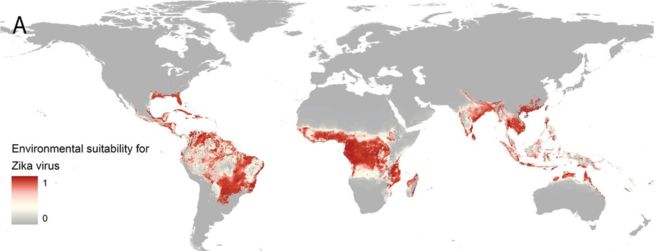

By learning where Zika could thrive the researchers could then predict where else may be affected. The researchers confirmed that large areas of South America, the focus of the current outbreak, are susceptible.

In total, 2.2 billion people live in areas defined as being "at risk".

The infection is suspected of leading to thousands of babies being born with underdeveloped brains.

The at-risk zones in South America include long stretches of coastline as well as cities along the Amazon river and its tributaries snaking through the continent.

And in the US, Florida and Texas could sustain the infection when temperatures rise in summer.

Dr Brady added: "Mosquitoes are just one condition needed for Zika to spread but there's a whole range of other ones.

"It needs to be warm enough for Zika to replicate inside the mosquito and for there to be a large enough [human] population to transmit it."

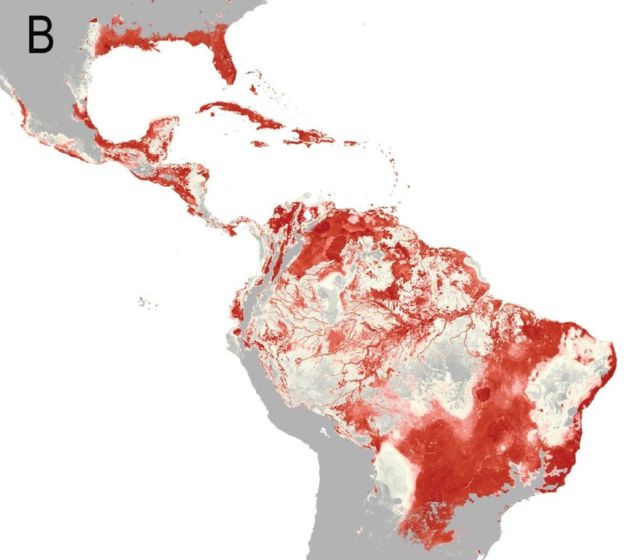

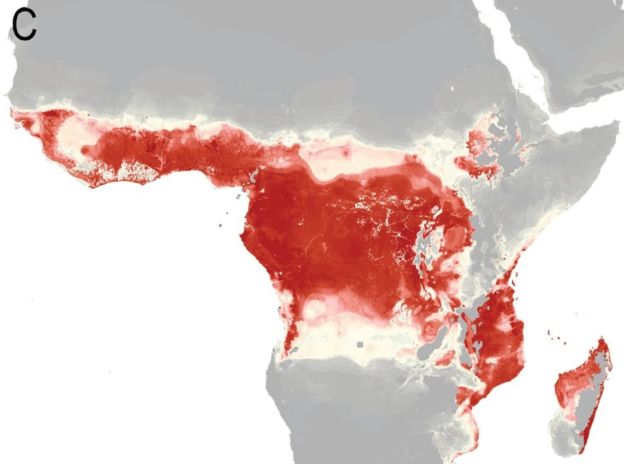

Both Africa and Asia have large areas that could be susceptible to the virus, the researchers said.

However, the study cannot answer why large numbers of cases have not already been reported.

One possible explanation is that both continents have already had large numbers of cases and the populations there have become largely immune to the virus.

An alternative is that cases could be being misdiagnosed as other infections such as dengue fever or malaria.

Europe seems likely to be unaffected, but that could change as more evidence emerges on which mosquitoes the viruses can spread in.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом