The forgotten wife of Charles Dickens

Catherine was an author, actress and cook – all of which was eclipsed by her marriage. Lucinda Hawksley, Catherine’s great-great-great-granddaughter, explores who she really was.

In February 1835, Charles Dickens had a party for his 23rd birthday. Catherine Hogarth, the daughter of his magazine editor, was one of the guests. “Mr Dickens improves greatly on acquaintance,” she wrote to her cousin after the party.

The improvement must have been dramatic: Catherine soon agreed to marry him.

Their wedding took place in London on 2 April 1836.

It was a marriage that would be both very happy and desperately sad. Over the next 15 years, Catherine would go through 10 full-term pregnancies and at least two miscarriages. And they went from a well-matched couple in love, enjoying parties and holidays together, to a couple unable to live in the same house.

Catherine would go through 10 full-term pregnancies and at least two miscarriages

In addition to being a mother, Catherine was an author, a very talented actress, an excellent cook and, in her husband’s words, a superb travelling companion. But as the wife of such a famous figure, all of that has been eclipsed.

With its new exhibition The Other Dickens, London’s Charles Dickens Museum has given Catherine back her identity.

As the great-great-great-granddaughter of Catherine and Charles, I’ve done my own share of research on the couple and their family. And I’ve come up with my own conclusions as to who Catherine really was – and what happened between her and Charles.

Much has been written about the Dickens’s marriage and the very public separation that occurred in 1858. In the early 20th Century, decades after both parties had died, the debate tended to be firmly on the side of Charles. Unpleasant rumours were started about why he ‘had’ to separate from her, with the reasons including that Catherine was an alcoholic (she was not).

Unpleasant rumours were started about why Charles ‘had’ to separate from Catherine

These rumours still occasionally persist, even in the 21st Century. Seldom is Charles Dickens permitted to be a real man with very real flaws. Instead he is written about as either a demon or a demigod, depending on the writer’s allegiance.

Catherine’s reputation, therefore, has accordingly been slotted into whichever opinion fits: she was either a persecuted martyr or an exhausting drain on the will of a great man. I am astounded by how many times journalists have asked me “So, do you side with Charles Dickens, as you’re related to him?” Each time, I have had to point out that, actually, I’m related to Catherine too – and that, where the producing of heirs was concerned, she did most of the work!

While writing my biography of their artist daughter Katey, I came to believe that the couple’s marriage ended for understandable reasons: it was put under unexpected, intolerable pressure by the rapidity of Charles Dickens’s ascent to previously unthought-of levels of celebrity.

When the couple met, Charles put Catherine on a pedestal. His childhood was scarred by poverty and the shadow of the debtors’ prison; in contrast, Catherine came from a comfortable, happy middle-class family. I believe Dickens wanted to emulate that: he wanted a wife and mother who would give his children stability and a carefree home. Catherine became his ideal woman.

When the couple met, Charles put Catherine on a pedestal

At the start of their marriage, Catherine was her husband’s social and financial superior, but within a very short time, Charles had gone from a journalist working for Catherine’s father to a man so famous that his works were read by Queen Victoria. Within a couple of years of their marriage, Charles’s views even had begun to affect the political views of their country.

As the wife of such a star, Catherine began to be overlooked. Meanwhile, while she was as happy as her husband at first, her multiple pregnancies – from which she barely got the chance to recover before getting pregnant again – began to take their toll on her health, energy and their marriage.

Now, for more than a century, Catherine has been marginalised and misremembered as a dull, frumpy wife. Even the sole Dickens biopic ever to have been made by the film industry focused not on Catherine, but on Ellen Ternan, Dickens’s mistress (a relationship that was ultimately the reason he separated from Catherine).

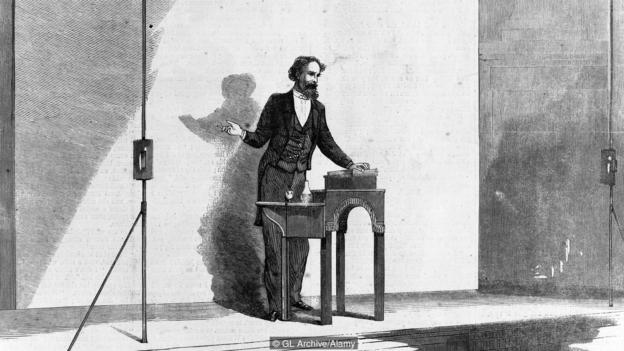

But the real story of Catherine is that of a fun-loving young woman who, as the wife of an international celebrity, travelled widely and had the opportunity to see and experience things that most women of her era and social status did not. She and Charles were very keen amateur actors, for example. Catherine not only performed in shows at home, but on stage in both the United States and Canada.

For more than a century, Catherine has been marginalised and misremembered as a dull, frumpy wife

Another of Catherine’s achievements? Publishing a book. When I researched it, I was infuriated to discover how many people – even respected academics – have claimed that it was written by Charles.

This view is intensely patronising, implying as it does that Catherine couldn’t possibly have had the intelligence to write a book. But it is also extraordinary to claim that Charles would have willingly added to his already punishing writing schedule only to publish a book under a female pseudonym – at a time when most female authors were being forced to write under masculine pen names in order to be published.

Catherine’s book is entitled What Shall We Have for Dinner? A guide for young wives more than a recipe book, it advises on household tasks and producing menus for up to 18 people. In essence, Catherine was the first Mrs Beeton – a decade and a half before the actual Mrs Beeton published her now-iconic cookbook.

Now, visitors to the Charles Dickens Museum have the chance to discover all of this – and the vibrant, witty and interesting woman who was ‘the other Dickens’.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом