Mystery of England’s: The strange, ancient tunnels to nowhere

More than a dozen tunnels have been found beneath Cornwall’s countryside, dating back some 2,400 years. But why do they exist?

“How do you like spiders?” asked James Gossip, an archaeologist, British prehistory expert and my guide to this subterranean world – one, apparently, that’s already inhabited. I looked at him, blanching slightly. He laughed. “Shall I just not point them out?”

“Maybe not,” I said, peering into the dark tunnel before us.

I’d come to nearly the very tip of Cornwall, the southwestern peninsula of England, in search of an ancient mystery: the underground passages built here some 2,400 years ago.

As a casual observer, you’d never know this part of the country had prehistoric surprises in store. Halliggye Fogou, on Cornwall’s Lizard Peninsula, is not only off the tourist track – it’s off any beaten track. The largest town within a 10-mile radius, Helston, has just 12,000 residents. The lush green hills are dotted with cows and itty-bitty villages lacking even a post box.

From this picture-perfect Cornish countryside, only a trained eye can pick out the complex tapestry of mounds, bumps and stones left by 150 generations working the land. “Do you see that, over where the windmills are?” Gossip asked me later, pointing to the nearly imperceptible humps on a hill in the distance. “That’s covered by Bronze Age barrows.” Enclosures – those bumpers of land that once surrounded a farm or settlement – are everywhere. And the landscape is littered with the remnants of roundhouses, stone circles and ramparts.

Gossip, though, is most interested in what people were building underground. Fourteen tunnels – called "fogous” after the Cornish word for cave “ogo” – have been found in Cornwall. Similar to the souterrains found in Scotland, Ireland, Brittany and Normandy, fogous haven’t been discovered anywhere else in England. Unlike, say, the labyrinthine copper mines tunnelled out 3,800 years ago in Wales, fogous (and souterrains) weren’t merely dug. They were built. To make them, it’s thought that people opened up deep trenches in the ground, sided them with stone slabs, topped them with capstones and filled in the area above them.

For an Iron Age society, this required a serious devotion of time and resources – and no one knows why they would have done so.

Some of the difficulty is that many of Cornwall’s fogous may already have been emptied. This may have been done by the people who actually used them. Or it may have occurred far later. “Many of them were excavated by antiquarians, so we don’t have many good records for what was found,” said archaeologist Susan Greaney, head properties historian at English Heritage, who specialises in prehistory. “There are only a couple that have been excavated in modern times – and they don’t seem to be structures that really easily give up their secrets.”

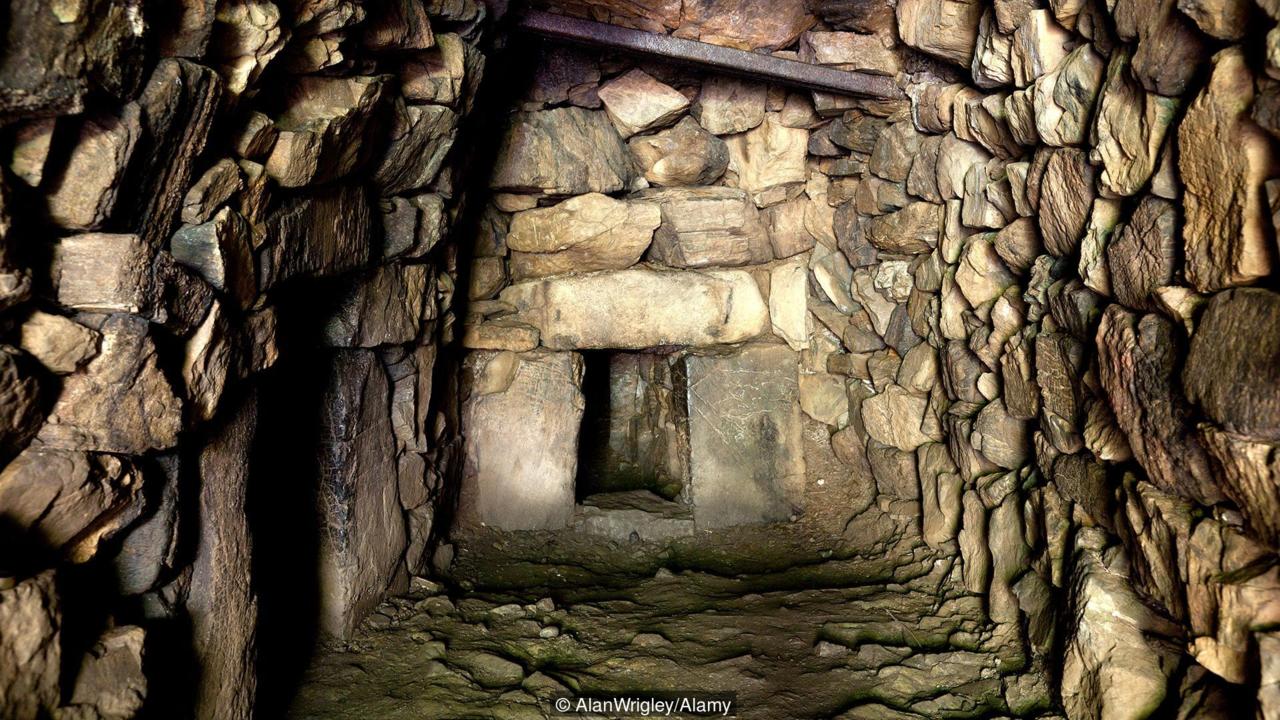

Take Halliggye Fogou, the best preserved fogou in Cornwall. Its first, 1.8m-high chamber is large enough to easily move around in. But at the end of the 8.4m passage, it abruptly narrows into another, 4m-long tunnel, one just 0.75m tall. “It’s something anyone would have to crawl along,” Gossip pointed out.

Another tunnel branches to the left off the entrance tunnel. At 27m, it’s three times the length of the first chamber – the distance of two double-decker buses laid end to end – and became progressively darker as we walked further inside. Darkest of all, though, was the final creep, tucked to the left of the end of the passage. Complete with a stone lip jutting up to trip you, the entrance was so narrow and awkward I had to put down my clunky camera in order to clamber through.

In other words, none of it seemed designed for easy access – a characteristic that’s as emblematic of fogous as it is perplexing.

“A lot of the discussion around fogous is what they were for, because they’re really strange,” Gossip said. “Many people talk about them as a place to hide.”

But as he switched off his torch, the likelihood of the hypothesis vanished along with the light. Damp, chilly, and the kind of black that modern-day humans don't tend to witness, it seemed a strange sort of hideaway for even the most desperate of times – or even with the most reliable of flames. “A person wouldn’t have wanted to spend much time in here,” he said.

Meanwhile, although these tunnels seem “secret” to us today, they weren’t necessarily then. Many have lintels that would have been visible from the surface, for example – making them an odd hiding place from intruders.

Over the years, other hypotheses have surfaced. Perhaps fogous were burial grounds: when Reverend Richard Polwhele recorded entering the Halliggye Fogou in 1803, he wrote that it “contained urns”. But the access hole that he made in its roof was used by other enthusiasts in ensuing years, and any urns are now gone. No evidence of burial, whether cremation ashes or bone, has been found in any of the six fogous that have been examined with modern archaeological techniques.

Were they used for storage? The soil is acidic, which helps explain the lack of organic material, like grain and bone. Still, it’s an impractical design for a cold store. As Greaney put it: “If you’re going to build an underground fridge, you’re going to want to be able to step in and out of it.”

And if fogous were used for valuables or metals – like local tin, perhaps – the quirky, yet likely still visible, design is odd; so is the fact that not a single ingot has been found.

The last prominent theory also seems unsatisfying, if only because it’s a frequent go-to for archaeologists who study a period as little understood as this one: maybe they were mainly ceremonial. Perhaps they were meant to be accessed only by the elite, with the restricted space echoing the restrictions of social class. Or perhaps they were places to commune with the gods.

“These were lost religions. We don’t know what people were worshiping,” Gossip said. But, he added, since they were often used over hundreds of years, their purpose probably shifted. And perhaps the real answer was all of the above: “There’s no reason they couldn’t have had a ceremonial, spiritual purpose as well as, say, storage.”

Richard Strachan, senior archaeologist for Historic Environment Scotland, manages the nine souterrains under the public body’s care. Archaeologists have faced many of the same conundrums there, from the odd shape of the tunnels (in Scotland, Strachan said, they’re banana-shaped, curving around a roundhouse, or in a cruciform) to the cleaned-out nature of their interiors. He agrees they probably had more than one use.

“I think they’re multi-purpose,” Strachan said. “Maybe seasonal, as well. Maybe you use them for storage, then when you don’t need them for storage, you use them for ceremony.”

Gossip is hoping that another site, located just three miles northeast of Halliggye Fogou, might reveal a bit more. Like many of the others, the Boden Fogou was found serendipitously – a farmer struck a pit while laying pipe in his field in 1991. Five years later, it happened again, his tractor opening up a hole in the ground. Both holes led to tunnels.

Ensuing excavations, which Gossip has run with volunteers each summer since 2003, have turned up not only an S-shaped fogou, but roundhouses and enclosures. In fact, every recorded fogou has been found within settlements.

One 3,400-year-old roundhouse that the team excavated was abandoned 300 years after its construction. It contained more than 3,000 artefacts, mainly shards of ceramics. In a pattern seen at other roundhouses in Britain, they weren’t where they would have fallen naturally – the shards seem scattered deliberately across the floor.

Some came from an enormous, elaborately decorated vessel at least 0.92m high. “It’s the largest Bronze Age vessel found in Cornwall, if not in Britain,” Gossip said.

The S-shaped fogou was dug 700 years after the roundhouse was abandoned, carefully skirting the roundhouse site. “When people come here in 400BC, they don’t disturb the place, perhaps out of respect,” Gossip said. About 500 years later, it too was deliberately closed, perhaps in a similarly ceremonial way. Early Iron Age pottery was placed on the bedrock floor, the roof was removed and dirt and stone from the surrounding bank shovelled in.

This is a pattern also seen with other souterrains. All of it seems to speak to a kind of closing ceremony. But for a structure built to do… what?

What, I asked Gossip, could he find in his excavations that might help answer the question? Is there a Rosetta Stone for fogous?

“I would like to find something that suggested a more ceremonial purpose,” he said. He paused. “But no matter what you found, there would still be discussion.”

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом