The strange tanks that helped win D-Day

When allied forces landed on the Normandy beaches on D-Day, they did so alongside a fleet of bizarre tanks with very special roles – brought into life by an eccentric British commander. BBC Future investigates.

On 19 August 1942, Allied armies put their plan for an invasion of Occupied Europe to the ultimate test – by landing troops on the beaches and trying to capture a French port.

France had, by this time, been under German control for more than two years. The landings at Dieppe would be a practical test to see if the Allied armies could land enough men and tanks to break the strong German defences.

The landings were a disaster.

In less than 10 hours, more than 60% of the 6,000 British, Canadian and American troops who landed on the beach were either killed, wounded or captured. All of of the 28 tanks which came ashore alongside them – essential if the troops were going to be able break through the German strongpoints – were knocked out. Many were stranded, unable to move on the loose shingle, and picked off by anti-tank guns.

The failure of the Dieppe landings provided many lessons. Trying to capture a heavily defended port was likely to fail, commanders realised. Troops would have to land on sandy beaches, and their tanks would have to be able to make their way across these beaches and punch holes through the seawalls or other concrete obstacles the Germans had built up.

One man, it turned out, had a solution. And two years later, his fleet of highly specialised – and often bizarre-looking tanks – would be one of the major reasons why the D-Day landings were a success.

Percy Hobart was a visionary British army commander. In World War One he’d served in France and Mesopotamia (now Iraq) and in the 1920s he began to realise the massive potential of tanks on the modern battlefield.

The first tanks were primitive, pioneering designs that lumbered at the pace of a walking man. They had only become available in the last two years of the war, yet they had proved decisive in some of the final Allied offensives against the German trenches. After World War One, freed from the constraints of trench warfare, tanks were becoming smaller, faster and more mobile. A new kind of tank warfare, more like the cavalry clashes of old, beckoned.

As Britain faced the threat of invasion, its leading expert on armoured warfare found himself demoted to corporal

David Willey, the curator at Britain’s Tank Museum at Bovington, says Hobart quickly became a leading light in this kind of warfare. In 1934, Hobart became the inspector of the Royal Tank Corps, and in charge of tank tactics. He was such an influential figure that Heinz Guderian, one of the leading commanders in Germany’s early victories of World War Two, had his reports translated and studied them intently, Willey says.

Hobart based his vision of fast-moving columns of tanks to the highly mobile Mongol hordes of the Middle Ages, and was one of the first commanders to predict that aircraft could help resupply these columns far behind enemy lines.

But after training a new armoured unit in the North African desert, Hobart was given early retirement – partly, it is thought, down to official hostility to his ‘unconventional’ views on armoured warfare. As Britain faced the threat of invasion, its leading expert on armoured warfare found himself demoted to corporal, and serving in the Home Guard in the Cotswolds village where he lived.

“At the museum we’ve got the ‘pike’ he was given – much of Britain’s military equipment had been left in France, so instead of a rifle he had a piece of scaffolding pole with a bayonet attached at the end. That’s what he would have used if the Germans had invaded.

“Montgomery, one of Britain’s most respected commanders, hears that Hobart has fallen out of favour; Hobart has a reputation for being a bit prickly, and has a tendency to rub some people up the wrong way.”

A meeting between Hobart and British leader Winston Churchill was convened; Willey says Hobart asked whether he should “turn up in his Home Guard uniform or his old army uniform”. After the meeting, Hobart was reinstated – and given the task of improving Britain’s tank force.

After the threat of a German invasion had receded after the Battle of Britain, thoughts turned to how a re-equipped British army could land on the beaches of France and fight it’s way further inland. The Germans had prepared an extensive line of defences – known as the “Atlantic Wall” – from the Franco-Spanish border to the north of Norway. Any beaches that could be used in a landing were guarded by concrete gun emplacements, strongpoints, trenches and anti-tank ditches – and enormous quantities of mines.

When the Allied armies invaded France on 6 June 1944, they did so along five beaches of the Normandy Coast. The troops landed alongside a fleet of specialised tanks that Hobart – learning from the costly assault at Dieppe – had helped design and bring into service. The tanks were known, collectively, as Hobart’s “Funnies”. On the British and Canadian beaches where they were used – Gold, Sword and Juno – the landings were a massive success.

Hobart had realised that an invading force would need a lot more tank support

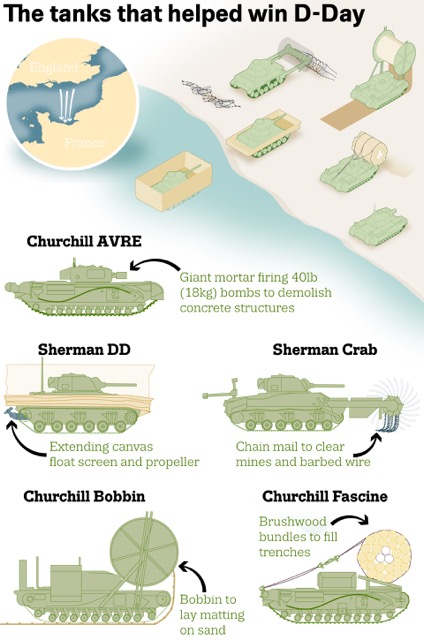

Hobart had realised that an invading force would need a lot more tank support – and they were most vulnerable when they were coming to shore. “If you put all your tanks in one landing craft, and that gets hit – how do you spread the risk?” The result was the Sherman DD (Duplex Drive) – the “swimming tank”.

There is a Sherman DD on display at Bovington, complete with a canvas screen that, once extended, helped make the tank float on water. The engine drove a propeller fitted at the rear, which allowed the DD to drive towards the shore at under 5mph (8km/h). The screen was designed to resist waves as high as 30cm – the crew, apart from the driver, often stood on the tanks hull to make it easier to jump off if it started to sink.

The tanks were supposed to be launched from their landing craft a couple of miles offshore to reduce the risk of being hit by artillery fire, but Willey says tests showed the tanks were more likely to survive in choppy waters if they were launched far closer to the shore. He says that the prospect of climbing into a 35-ton tank that would sink like a stone if anything went wrong must have been nerve-wracking enough in rehearsals – to do so under fire must have been truly terrifying.

On D-Day, most of the DDs landing with British and Canadian troops – on Gold, Sword and Juno beaches – were launched close to shore; the sea was choppier than expected, and the commanders decided to bring the landing ships closer to the beach to give the DD tanks a better chance of reaching shore.

But during the American landings – code-named Utah and Omaha beaches – the DDs fared far worse. Willey says the US commanders stayed rigidly to the original plan, launching their tanks from at least two miles away. At Omaha, most of the DD tanks launched sank in the choppy waters.

The DD tanks that landed on the other beaches, folded up their canvas screens, and were then able to fight like a conventional tank. Behind them came more of Hobart’s unique creations, each of them with a particular task.

The Sherman Crabs would push their way through the minefield, and they would also rip their way through any barbed wire as well – David Willey, Tank Museum

Among the most dramatic was the Crab. This was a Sherman tank with a flail at the front – a giant drum containing chains that spun at more than 140 rpm, beating the ground. The impact would detonate any mine in front of the tank, and other tanks or infantry could safely travel behind.

“The Sherman Crabs would push their way through the minefield, and they would also rip their way through any barbed wire as well – which was a bit of a bonus,” says Willey.

“The flail crews were told that if they didn’t clear a hole, then the massive invasion behind them would fail. That’s quite a lot of expectation.

It wasn’t just the German defences that would cause problems – the very beach itself could be an issue. Part of the preparations for D-Day, Willey says, was for recon parties to land on the beaches and collect sand, to see if the beaches were firm enough for tanks.

“When they did their training, they tried to find beaches that had the same geological set-up,” says Imperial War Museum senior curator Paul Cornish. “A certain kind of sand they encountered, which they called blue clay, caused all the vehicles to bog down.”

Again, Hobart and his team had a solution; the Churchill Bobbin. The outlandish modification of Britain’s main tank had two arms in front of the tanks carrying an enormous bobbin of canvas matting – as the tank drove forward it unrolled the matting, creating a carpet for a tank to drive on. The carpet was nearly 10ft (3m) wide and more than 200ft (60m) long.

The German defenders would have had no idea what was going on

“It’s one of the most extraordinary vehicles of the war,” says Cornish. “If you can imagine what it would have been like for the German defender, seeing this crawling up the beach. They would have no idea what was going on.”

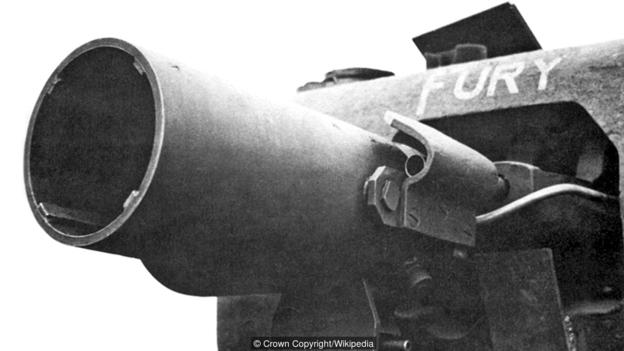

More Churchills had been modified to carry a ‘petard’; a huge, heavy mortar firing shells to shatter concrete. The AVRE (Armoured Vehicle Royal engineers) Churchills weren’t designed to fight other tanks, but to fire at concrete bunkers or even the concrete sea wall itself, blasting holes that troops and other tanks could then stream through.

Willey says the effect of the AVRE was more than just physical. “You have this huge mortar which fires shells the size of a dustbin. The explosions are enormous. There’s a real psychological factor with weapons like these.” The AVRE’s became even more valuable inland, with the mortar particularly effective in urban areas.

The ingenuity of Hobart’s vehicles continued. Many Churchills trundled onto the Normandy beaches carrying a fascine – a huge bundle of sticks that could be dropped into a ditch and allow a tank to drive across. Tanks had already used such a technique during the trench warfare of World War One, but the concept was nothing new – fascines had been used to bridge ditches right back to Roman times.

“So many times, these issues come back in different issues, but the fundamental issues remain the same,” says Willey. Hobart’s genius, he says, was his ability to be open to ideas – and even the most old-fashioned solutions could be reworked to match the needs of a modern army.

The “funnies” also included a range of bridging tanks – some Churchills carried a girder bridge that could be placed over a wide ditches or water crossings, which was strong enough to carry the heaviest tanks.

“These bridges would be used to replace bridges that had been destroyed in the fighting,” says Cornish.

Other engineers manned armoured bulldozers, which could push wrecked tanks out of the way or clear paths through rubble

And for high sea walls there was the Churchill Ark. The Ark had no turret, and was equipped with ramps on the front and back. It was driven up to a seawall or high obstacle, and other tanks would simply drive over it.

Other engineers manned armoured bulldozers, which could push wrecked tanks out of the way or clear paths through rubble. They could also place demolition charges against obstacles which could then be detonated from a safe distance.

More Churchill tanks, nicknamed “Crocodiles”, carried flamethrowers. Like the AVREs, these could often break resistance without huge loss of life – the prospect of being burned alive was often the final straw for German defenders. “Sometimes you would get the Crocodiles moving up and testing their flame thrower with a few practice squirts – and the Germans would surrender without another shot being fired,” says Willey.

Weapons like the AVRE and Crocodile might seem barbaric, but Willey says Hobart was aware that their deployment could save lives on both sides. By the time the Normandy landings took place, Britain had been at war for nearly five years. “In the run-up to the invasion, Montgomery, the British commander, had had to amalgamate lots of units because, quite simply, we were running out of blokes.”

For the “Funnies”, D-Day was only the beginning. Many of the vehicles proved perfect for the campaign in the Normandy bocage, which took place in narrow lanes sided by dense woodland. American forces, which had initially thought Hobarts creations were too bizarre for combat, ended up using them as much as the British.

The “Funnies” were farmed out in small groups wherever they were needed, a flexible approach which only added to their effectiveness

By the end of the war, the 79th Armoured Division – the unit which controlled the “Funnies” – “was the biggest armoured unit in Europe,” says Willey. The “Funnies” were farmed out in small groups wherever they were needed, a flexible approach which only added to their effectiveness.

“The other great thing about the ‘Funnies’ is that, apart from the drivers, they were crewed by Royal engineers. These really are the experts. One of the great strengths of the British Army in Normandy is they have this engineering and bridging expertise,” says Cornish.

Hobart, says Willey, was a man “who makes things happen. He’s the right man at the right time. And he’s very determined.”

“There are all these stories of him getting in his car and driving at breakneck speed late at night to turn up somewhere where something was being tested – ‘You will have this up-and-running by tomorrow, won’t you’ – and getting things done through force of will.”

“But he was also a man who would take a good idea from anyone. It didn’t matter if you were a corporal, or a retired major-general, or a scientist – if you had a good idea, he’d listen to it.”

Seventy years after the end of World War Two, most armies use specialist armoured vehicles that wouldn’t have looked out of place in Hobart’s ragtag armada of bizarre creations. The “Funnies”, it turns out, were no joke at all.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом