Why German mistrust made Hitler’s Mein Kampf a bestseller again

As Adolf Hitler's intellectual property rights were about to expire last year, Germany faced the agonising choice of how best to deal with the writings of the man at the heart of the darkest chapter of its history.

For the previous 70 years, the Finance Ministry of the State of Bavaria had exercised Hitler's intellectual property rights. In doing so, it had prevented republication of Hitler's notorious anti-Semitic political treatise, Mein Kampf (My Struggle) in Germany.

Germany faced the choice of following the liberal approach favoured by the UK, US, Canada and Israel, trusting and leaving it to civil society to engage with Mein Kampf. Another option was, as Austria and other countries had done in the past, to issue an outright ban of Hitler's book.

In the event, Germany rejected both options, favouring a heavily paternalistic approach instead.

What is Mein Kampf?

Originally printed in 1925 — eight years before Hitler came to power

Edited by Hitler's deputy, Rudolf Hess, it outlines his political ideology

It includes future plans for Germany, including Lebensraum, the need to colonise neighbouring territory to allow Germany to achieve its full potential

Copyright after World War Two was given to the state of Bavaria, which refused to reprint the work to prevent inciting hatred

That copyright expired at the end of 2015 and the new edition has sold tens of thousands of copies

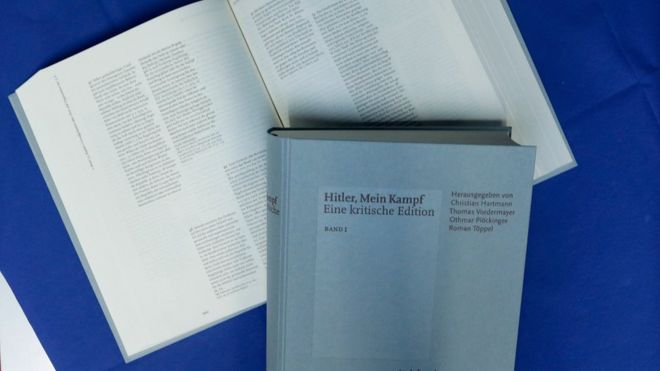

The State of Bavaria gave half a million euros to the Munich-based Institute for Contemporary History (IfZ), a semi-state-run research institute, in order to produce an annotated critical edition of Hitler's book.

At the same time, it stated that it would take anybody to court if they published editions that were not annotated. In a further twist, the Bavarian government cleverly tried to create the impression that it had withdrawn financial support for the annotated edition of Mein Kampf, thus leaving the IfZ to stand alone in the rain.

Failed strategy

As January 2016 neared, and with it the IfZ's publication of Mein Kampf, the Munich institute as well as German government officials were becoming highly nervous of what was about to happen.

The institute said at the time how dangerous it would be if Mein Kampf turned into a bestseller in Germany.

Yet, at the same time, it assured the public that would never happen. Its director, Andreas Wirsching, declared that it would be irresponsible to hand over Mein Kampf "free of copyright and commentary", because in that case everybody could do whatever they wanted with Hitler's book.

The IfZ indeed had produced an edition that was unlikely to fly off the shelves.

Weighing in at 5.4 kg (12 pounds) and including 3,700 footnotes, it is a great piece of scholarship.

Even for experts it is extremely tedious to read.

And for several weeks it was next to impossible to buy copies of the book, as the Institute for Contemporary History had opted for a very low initial print-run.

Subsequent printings took an oddly long time to arrive at book shops.

However, the paternalistic approach favoured by the Munich institute and by German authorities failed dismally in trying to prevent Mein Kampf from turning into a bestseller.

Pole position

All they did was postpone the appearance of Hitler's book in the German bestseller lists.

If anything public interest in the book was fanned unnecessarily by keeping the aura of the forbidden alive.

By mid-April, Mein Kampf had managed to move to the pole position of Germany's influential Spiegel bestseller list, where it remained for several weeks.

Even now it stands in 14th place, though many bookshops do not have the book on display and others only order the book on request.

The German approach may have failed but, arguably, concerns about the likely dire consequences of Hitler's book turning into a bestseller were unfounded.

There are no signs that the overwhelming majority of people buying Mein Kampf are doing so for any other reason than curiosity and genuine interest.

There is no reason to believe that in a year's time or so, when the first excitement about the whole affair will have evaporated, Mein Kampf will be more popular in Germany than in Britain or America.

One may also raise the question, as I have in German daily Die Welt, whether Germany would not have been served better by following the liberal approach favoured by the Anglo-Saxon world, rather than a paternalistic approach that distrusts civil society.

Indeed one may also ask whether Mein Kampf becoming a bestseller, and thus Germans engaging with their past, is really such a bad thing, when politicians around the world are frequently compared to Hitler and at a time of resurgent political populism akin to the 1920s.

The fear expressed in Germany and elsewhere is, of course, that Hitler's book may prompt a new wave of anti-Semitism and a resurgence of the radical right.

That concern was fanned further by the announcement by radical right-wing East German publishing house Schelm that it would issue a version of Mein Kampf without annotation. The state of Bavaria has asked prosecutors to take the publisher to court.

Schelm's announcement should be seen as a publicity stunt, similar to the decision last week of Italian daily Il Giornale to hand out free copies of Hitler's book.

But these stunts only became possible because the Bavarian government decided to prevent republications of Mein Kampf for 70 years and they are unlikely to have a lasting effect.

Neo-Nazis and their sympathizers have been able easily to access Mein Kampf on the internet for years and thus are unlikely to be affected by the return of Mein Kampf in print.

In fact, there is no correlation between the approach different countries have taken in the past towards access to Mein Kampf and the respective strength of extremist movements in the countries involved.

It could be argued the danger lies elsewhere: that it is the paternalism shining through the German approach to the republication of Mein Kampf, rather than Hitler's book itself, that fans right-wing populism.

As German intellectual Nils Minkmar warned in Der Spiegel, cultural arrogance and a "haughtiness towards poorly educated classes" has been leading to "the alienation of the lower classes from liberal society", and thus to the resurgence of right-wing populism in the country that Hitler once ruled.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом