Is this a perfect city?

History is full of failed attempts to create the ideal town. Is it possible to buck the trend? Jonathan Glancey finds out.

Chandigarh, India’s most prosperous and greenest city, was born of dreams at the time of one of the country’s worst nightmares. In 1947, India gained its independence from Britain. As part of this process, the country was divided in two and some 14 million Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims were displaced. Ethnic tensions and rivalries led to up to around a million (estimates vary) brutal murders.

In the Punjab region, the dividing line between the two states meant that the old capital, Lahore, was now a part of Pakistan. In 1949, Chandigarh was decreed. Not only would this be the capital of Indian Punjab, but it would be the very model of a modern city promising peace, democracy and a new social order free of bitter divisions.

The town promised peace, democracy and a new social order

But, what would a modern Indian regional capital be like? Who would plan it? At the time, the United States was the world’s most overtly modern democratic country, so Indian politicians and bureaucrats looked there for expertise. The New York planner Albert Mayer, already advising Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first prime minister, came up with a scheme for the new city in the foothills of the Himalayas that fused Modern Movement and Garden City ideals.

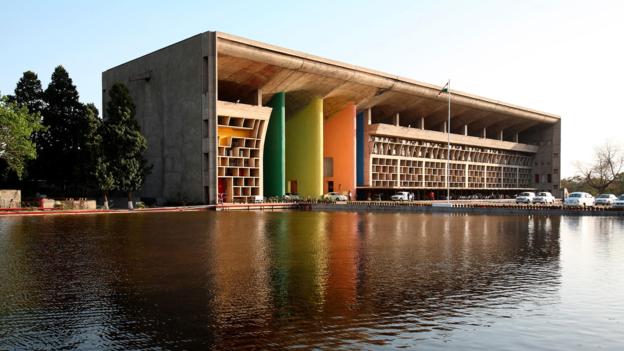

ET0NMD High court building of Chandigarh Union Territory India

In 1950 however, Mayer’s talented principal assistant Matthew Nowicki was killed in an air crash, at the same time as the value of the US dollar was rapidly rising. Nehru and his advisors began to look elsewhere. An Indian delegation went to see Le Corbusier, the renowned Swiss-French architect, in his Paris atelier. Corbusier had long dreamed of creating an ideal city, and although initially unsure, agreed to take on the planning of Chandigarh along with the design of its principal buildings.

Ghost towns?

Fifty years on from le Corbusier’s death in 1965, the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patromoine, the Paris gallery and archive housed in the Palais du Chaillot, has put on a show that includes superb new photographs of life in Chandigarh, posing the question: did the architect succeed in shaping a truly habitable ideal city?

EGWXMM Chandigarh, Punjab University, Gandhi Bhawan Reflecting On Water, Le Corbusier

The question is especially important now, given the world’s rapidly increasing population and the accelerating drift of people from countryside to cities. Should we tinker or somehow revamp existing cities to cope, or should we build new places to dwell?

History is littered with failed ideal cities

History, however, offers words of warning: it is littered with failed ideal cities. While we do not know exactly how, where, when and why the very first cities emerged, it seems likely that, to begin with, they grew organically. Yes, there were clearly moments in their history when grand new city centres with great, civic, religious and military monuments were decreed, yet often when cities have been conjured this way, they have ground to a halt, or turned into dust.

When, for example, Pharaoh Akhenaten decreed a new capital city in 1346BC, his subjects were unconvinced by his dramatic gesture. Not only was Amarna an entirely new city, it also represented the overthrow of Egypt’s ancient religious culture. Akhenaten – father of Tutankhamun and husband of Nefertiti – had created his own monotheistic religion, confining the old gods to history.

DE4H3R View of the of the sunken garden of the northern section of the Harem Quarter of the Great Palace at Amarna.

This was as shocking as the speed at which his new city was built. Within less than five years, Amarna was complete. Such was the speed of its construction that most buildings were raced up in mud-bricks with only the most prestigious faced in stone. As a result, after Akhenaten’s death and along with the demise of Aten and the return of the old gods, Amarna was abandoned and fell into instant decline.

Three thousand years later in India, the Mughal emperor Akbar moved his capital from Agra to Fatehpur Sikri. In contrast to Amarna, this ideal city was beautifully built, its imaginative monuments carved fastidiously from richly coloured stone. There was one snag: water, or a lack of it. For all its architectural magnificence, Fatephur Sikri was the Mughal capital for just 15 years. In 1585, Akbar moved on to Lahore. Ever since, his dream city has been a ghost town, although its buildings survive intact.

When the Venetian Republic decided to build an ideal town in 1593, there was no lack of water and no argument over religion. And, yet, although Palmanova was seemingly perfect – a fortified town built in the shape of a nine-pointed star with wide streets radiating from its handsome centre – it was an abject failure. Military aside, no one wanted to settle here. Seventy miles north-east of Venice, Palmanova was out in the sticks. A decree of 1611 freed Venetian criminals willing to settle there.

F0297C Aerial view of Palmanova — Province of Udine, Friuli-Venezia Giulia Region, Italy

Palmanova survives, and yet for all its mathematical elegance and utopian beauty, it remains more an exquisite curiosity than a model of how to build an ideal new town. What it lacked, along with Fatehpur Sikri and Armana, was commitment from ordinary people, from the merchants, market traders and craftsmen with their gift of quotidian urban life.

Best laid plans

Plans for ideal cities have often been shelved, among them Sir Christopher Wren’s design for a rational new, Renaissance-style City of London following the Great Fire of 1666. Merchants, bankers and traders keen to get back to business had no interest in waiting while some ideal, and no doubt costly, new city was built around them. Wren’s nobly intended plan was consigned to the archives.

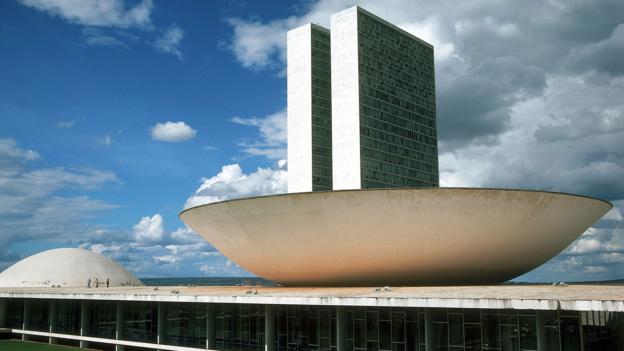

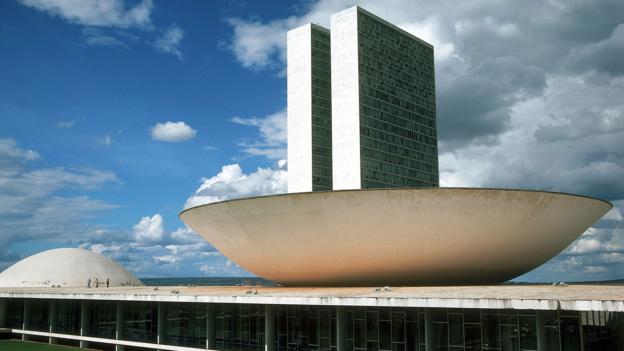

B489BY geography/travel, Brazil, Brasilia, building, of National Congress, (Congresso Nacional), built 1956-1960, by Oscar Niemeyer, (*

A few have more or less succeeded. Despite a dismal start, St Petersburg – a dream of the Peter the Great – rose from malarial swamps besides the Baltic Sea to become Russia’s imperial capital. Even then, Moscow regained the title, and although its 18th Century centre is hauntingly beautiful, St Petersburg’s history is as dark as it is poetic. It has even been unsure of its name, being known variously as St Petersburg, Petrograd and Leningrad in its short, dramatic life.

Ideal towns lack the layers of history and culture of organic cities

Brasilia, the modern city decreed by the Brazilian president Juscelino Kubitschek, and designed and built within just four years (1956-60) by Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa is a futuristic wonder, and yet its working classes live not in sleek, central apartment blocks, but in a ring of shanty towns.

F3FM9D An aerial view of modern housing, Milton Keynes, South East England, UK

As for Britain’s much vaunted New Towns, Milton Keynes – the last and the biggest – is perhaps the best. Laid out on a generous grid of avenues, for the most part it is much liked by those who live here. For those in search of the life London can offer, however, Milton Keynes will never do. Like most ideal towns and cities, it lacks the layers of history and culture of organic cities.

Of all the world’s ideal cities, Chandigarh has done remarkably well, offering striking monumental architecture, a grid of self-contained neighbourhoods, more trees than perhaps any Indian city and a way of life that juggles tradition with modernity. While history tells us ideal cities are mostly best left on paper, Chandigarh – perhaps one of the least likely – appears to have succeeded against the grain.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом