Why Syria Election Will Hand Assad Victory

There won’t be much need to stay up late to find out the results of the April 13 parliamentary elections in Syria as the outcome is a foregone conclusion, say opposition politicians and independent election experts, who dub next week’s wartime poll a PR stunt.

The elections being held next week in Syria — or at least in government-controlled areas — won’t be nail-biters, they say, and will see the ruling Arab Socialist Ba’ath Party of President Bashar al-Assad and its political allies storm to inevitable victory, thanks to a careful selection of candidates and the fact that the polls will only be held in regime-controlled districts.

French President Francois Hollande has dubbed the elections “provocative" and “totally unrealistic.”

And the main Western-backed political opposition to Assad, the Syrian National Coalition (SNC), has called on Syrians in areas where they can vote, to boycott the polls, arguing the country’s five-year-long civil war won’t be ended “through unilateral projects” but only by a negotiated political transition involving all Syrians.

SNC officials argue the election is an effort by Assad to project a political legitimacy he doesn’t have — part of a bid to rehabilitate his regime in the eyes of the international community.

Lots of candidates = free elections?

Just before the cessation of hostilities was negotiated in February, President Assad announced his intention to hold parliamentary elections on April 13, issuing a decree for polls to be held for the country’s 250-member legislature, known as the People’s Council, whose members are elected for a four-year term.

In the last few days in regime-held areas — especially in the capital Damascus — streets have been plastered with campaign posters by the almost 12,000 candidates competing for seats. President Assad has pointed to the “unprecedented” number of candidates as evidence that the elections are anything but a sham.

Ba’ath party official Wael al-Imam argues it demonstrates Syrians “believe in democracy and will use the chance to make their voices heard in a free manner.”

But independent election experts say there is little free or fair about these elections. “It would not be in line with any international standards,” says Vladimir Pran, a consultant for the International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES), a Washington-based non-profit that provides technical assistance for elections in new and emerging democracies. IFES frequently partners with the United Nations to organize post-conflict elections.

“No one in the international community will recognize the April polls,” he told VOA when Assad announced his intention to hold the polls.

Candidate screening, other hurdles

Next week’s polls will be the third time the regime has held elections since the uprising against Assad erupted.

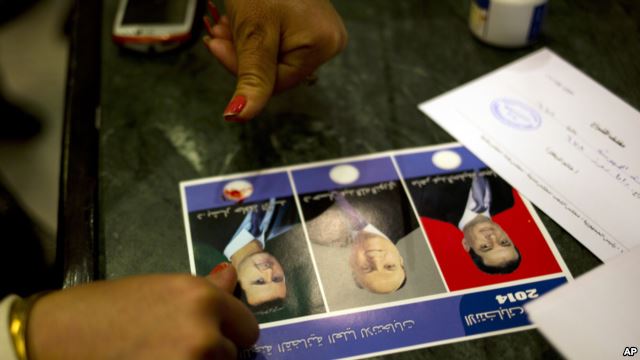

In 2012, the country held parliamentary elections, and in 2014, there was a presidential poll. The 2012 vote was the first since the ruling Ba’ath Party came to power in 1972 that allowed non-Ba’athist candidates to run — a reform highlighted by the regime, which said the introduction of a multi-party contest was an historic step.

But candidates still had to go through a careful screening process to be eligible to stand.

The same is the case with next week’s polls.

Half of Syria’s parliamentary seats are reserved for laborers and farmers who have no party affiliation. Various committees whose members are appointed by either Assad himself or provincial governors, determine who is a non-affiliated farmer or laborer.

Candidates also have to jump through other hurdles to get on the ballot paper, further undermining the democratic nature of Syrian polls, say Assad opponents.

In addition, the Ba’ath party and political allies benefit from a block vote system used in Syrian elections, says Pran and other election experts.

Several seats are assigned to each constituency. Under Syria’s current law, the voter has up to as many votes as seats available and the candidates with the highest vote totals win the seats.

This gives an advantage to the more developed and established parties — in Syria’s case, the Ba’ath party. Even in a free and fair election environment, the block vote system works against the opposition if it is fragmented, as it is in Syria, and gives the party that has even a slight lead in the popular vote an overwhelming number of seats.

Presidential election?

In 2012 most of the 250 parliamentarians elected were Assad supporters, either Ba’ath members or of groups aligned with the ruling party. In that election the Ba'ath party and its allies won 168 seats in the 250-seat legislature. The opposition received just six seats with the remainder going to non-partisan farmers and laborers, most considered regime placemen.

But as in 2012 and 2014, the regime will likely point to next week’s polls as evidence of the legitimacy of Assad’s rule. In the brief election campaign that has been allowed in the run-up to next week’s polls, no major criticism of Assad has been launched by the candidates vying for to secure a seat, say political activists.

That is hardly surprising. To do so would risk arrest. Under Syria’s penal code, it is illegal to make public statements that “weaken national sentiment.”

On March 31, Assad raised the possibility of holding an early snap presidential election, too, telling a Russian media outlet that he was ready to do so, if the Syrian people wanted it. "This depends on the Syrian people’s stance, on whether there is a popular will to hold early presidential elections,” he said. Assad didn’t explain how that “popular will” would be communicated.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом