The turning point in the battle against IS?

The international campaign against the so-called Islamic State (IS) group is evolving quickly. As the United States announces a new phase in its campaign, shifting from "degrading" the so-called caliphate to destroying it, the key questions concern what the extremist group will do to thwart the campaign.

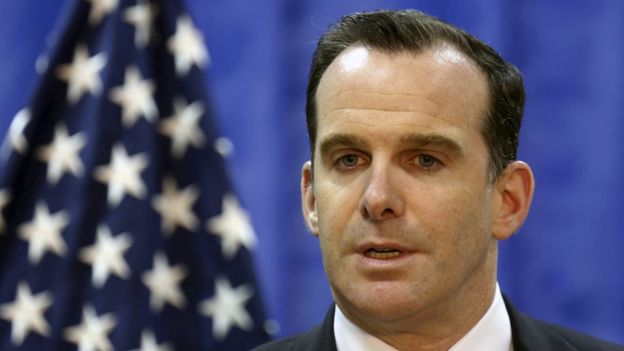

"The trend lines which were all going the wrong way are now going the right way," argues Brett McGurk, the Special Presidential Envoy or White House point man for the anti-IS battle. I recently spoke to him and Didier Le Bret, France's National Intelligence Co-ordinator, at the Aspen security conference in London. So what indicators convince them that the battle is turning?

Both cite recent territorial losses by IS, financial problems, and more effective sealing of the routes in and out of their "caliphate" in Iraq and Syria.

"It's a lot harder to get into Syria and once these guys get into Syria it's more difficult for them to get out," says McGurk. This impression is backed by Pentagon statistics released this week suggesting there are now about 200 foreign fighters reaching IS in Iraq and Syria each month compared with 1,500-2,000 a month one year ago.

Turkey says it has stopped 44,000 suspected militant sympathisers from crossing into Syria or Iraq, and the impression that domestic intelligence services in France have formed is that's some of those who have failed to get in joining others who have become disillusioned coming home.

"We have a lot of French people who are coming back," says Ambassador Le Bret. "They are coming back, which means that it's not like at the beginning."

A series of steps has helped to hit IS financially: oil facilities it used for income have been hit, government salaries to those in IS-held areas have been cut by Iraq and Syria, and when it comes to foreign remittances, "we think we have pretty much sliced that off," says McGurk.

As a consequence, the group has halved its fighters' pay and has tried to come up with revenue-raising schemes, from new taxes to parking tickets.

Avoiding triumphalism

There are clear signs that the Obama administration is trying to accelerate the group's demise. This week it announced an additional 250 troops could be sent to Syria, and long-range artillery (the HIMARS missile system) is reportedly being deployed in Turkey and Jordan.

As Iraqi army units begin their long-awaited push on the city of Mosul, US military advisers are to be attached at a lower level, in part so they can back them up by bringing in artillery fire and air strikes.

As US numbers build in Syria, special operations forces, often accompanying Syrian proxy groups, are stepping up their missions against the leadership of IS (also known as Isil). "We're now striking a leader of Isil around every three days," McGurk reveals.

"We're deep inside the network and beginning to unravel it."

The American special operators are also supporting contingents of Kurdish and Syrian militias on the ground, as recently emerged video shows.

All of this suggests an increased appetite for risk on the part of the Obama administration, which long baulked at putting troops in Syria or accompanying low-level Iraqi operations. The White House has apparently glimpsed the possibility that rolling back, or even crushing, IS might be attainable as a "legacy" item for the president.

Having charted recent progress, however, most people involved with the fight are keen to scotch any triumphalism. There are many obstacles still to the final defeat of IS, and the group has many cards it can play.

The faltering Syrian peace process, and governmental disarray in Baghdad could help convince many Sunnis in IS-held areas that there is no real choice but to stick with the group.

The Libyan dimension

The freeing of some areas from IS control has set off clashes between Kurdish and Shia factions — and there must be a chance that the fall of Raqqa or Mosul would lead to an orgy of destruction, fighting over the spoils, and revenge.

Given the extensive reliance of their strategy on proxy forces, isn't such a scenario highly possible? I asked Special Presidential Envoy McGurk

"You can never completely eliminate what you're talking about, the lawlessness, the tit-for-tat revenge type events," he explained. "The post-Isil phase, which will be just as challenging."

This prognosis suggests the possibility of Libya-style anarchy and — of course — it is the ungoverned space in that North African country which now appears to provide IS with a Plan B.

"Where we do get concerned, however, is where we see the transfer of money, the transfer of messaging instructions, and the transfer of leaders and we have definitely seen that in Libya," McGurk reveals. "Libya is an increasing focus of ours."

French intelligence boss Le Bret sees an expanding IS role in that country as a nightmare that could destabilise all of North Africa, arguing: "If we let Libya become a safe harbour for Daesh [the Arabic acronym for IS], this is going to be really, really, hard for us to correct that in the long run."

Of course for the French and other European security services it is another kind of shift that now concerns them most: the prospect of more terror attacks on the Paris and Brussels pattern. "The more efficient we will be on the ground, the more aggressive they will be around Europe," argues Le Bret. "This is the easiest fix for them."

The flow of returning fighters detected in France could carry with it many men intent on unleashing violence in Europe, as their "caliphate" falters. Le Bret's US intelligence counterpart, James Clapper, this week confirmed an assessment that IS had sleeper cells in the UK, Germany and Italy, saying that "they have taken advantage, to some extent, of the migrant crisis in Europe".

It is the realisation of what may lie ahead that leads McGurk to characterise the next phase of the fight as "extremely difficult". Le Bret, also cautious, notes that while he thinks victory is certain, "this is not a war that you can win in a couple of years or five years".

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом