If no-one helps you after a car crash in India, this is why

When a road accident occurs, bystanders will usually try to help the injured, or at least call for help. In India it's different. In a country with some of the world's most dangerous roads, victims are all too often left to fend for themselves.

Kanhaiya Lal desperately cries for help but motorists swerve straight past him. His young son and the splayed bodies of his wife and infant daughter lie next to the mangled motorbike on which they had all been travelling seconds earlier.

The widely broadcast CCTV footage of this scene — showing the suffering of a family of hit-and-run victims in northern India in 2013 and the apparent indifference of passers-by — troubled many Indians.

Some motorcyclists and police eventually came to the family's aid but it was too late for Lal's wife and daughter. Their deaths sparked a nationwide debate over the role of bystanders — the media hailed it as a "new low in public apathy" and worse, "the day humanity died".

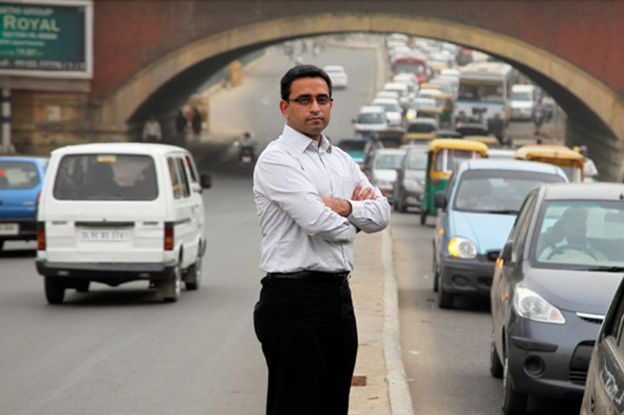

But what safety campaigner Piyush Tewari saw wasn't a lack of compassion but an entire system stacked against helping road victims.

His work to change this began nearly 10 years ago, when his 17-year-old cousin was knocked down on the way home from school.

"A lot of people stopped but nobody came forward to help," Tewari says. "He bled to death on the side of the road."

Tewari set out to understand this behaviour, and found the same pattern repeated time and again across the country. Passers-by who could have helped were holding back and doing nothing.

"The foremost reason was intimidation by police," he says.

"Oftentimes if you assist someone the police will assume you're helping that person out of guilt."

The discovery spurred Tewari to set up SaveLIFE. In a 2013 survey, the foundation found that 74% of Indians were unlikely to help an accident victim, whether alone or with other bystanders.

Apart from the fear of being falsely implicated, people also worried about becoming trapped as a witness in a court case — legal proceedings can be notoriously protracted in India. And if they helped the victim get to hospital, they feared coming under pressure to stump up fees for medical treatment.

In a country with smoothly functioning emergency services, bystanders often need to do little more than call an ambulance, do their best to provide first aid and reassure victims that help is on the way.

But in India ambulances are in short supply, sometimes very slow to arrive and often poorly equipped. This makes it a country in need of Good Samaritans — and according to Tewari there are many Good Samaritans out there. They just choose carefully when to leap into action.

He contrasts the reluctance of passers-by to help victims of road accidents with their response to train crashes or bombs blasts.

In these cases, he says, "before the police or media arrives everybody's been moved to hospital".

The big difference with road accidents is that there are usually just one or two victims. "The chances of getting blamed are much higher," he says.

SaveLIFE filed a case with India's top court to introduce legal protection for Indian bystanders and a year ago there was a breakthrough when the Supreme Court issued a number of guidelines, including:

allowing people who call to alert emergency services about a crash to remain anonymous

providing them with immunity from criminal liability

forbidding hospitals from demanding payment from a bystander who takes an injured person to hospital

Just two months later, though, another hit-and-run incident caught on camera shocked the nation.

"See how they're just watching?" murmurs Anita Jindal as she scans the CCTV footage, once again, on her mobile phone in the cramped room-cum-corner shop she once shared with her son, Vinay.

A speeding car had hurled 20-year-old Vinay off his scooter in east Delhi, and the footage shows a crowd of onlookers surrounding him, and doing nothing.

It went viral on social media last July, triggering a new bout of soul-searching, and was even mentioned by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in his monthly radio broadcast to the nation.

"If someone had helped he may have been here today," says Anita Jindal. "Everyone told me they were scared of the police."

For Piyush Tewari and SaveLIFE the struggle goes on.

In March the Supreme Court guidelines were declared compulsory. To ensure that they will be enforced, the foundation is now campaigning to get each of India's 29 federal states and seven union territories to enshrine them in a Good Samaritan law.

Fifteen people are killed every hour in road accidents in India

Twenty children are killed every day in road accidents in India

One million people have died in road accidents in India in the past decade

Five million people were seriously injured or disabled in road accidents in India in the past decade

The equivalent of three per cent of GDP is lost annually due to road accidents

Shrijith Ravindran, the chief executive of a restaurant chain, is one person for whom this legislation cannot be introduced soon enough.

In January he came across an elderly man bleeding by the roadside in the western Indian city of Pune. A gathering crowd of people was still deliberating what to do when Ravindran put the man in his car and drove him to hospital.

The closest hospital gave him a bunch of papers to fill in before turning him away.

The next one swamped him with more paperwork before tending to the patient.

In total, he says, he spent three hours filling in these forms.

"They ask, 'Are you a relative?' The moment you say 'No', they don't do anything," says Ravindran.

"They wait for somebody to give them assurance that they will pay the bill. Valuable time is lost."

The elderly man finally received treatment once the paperwork was completed, but it was too late. He died of his injuries.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом