A tiny country of creative geniuses

Scotland has long been at the forefront of innovation, drawing on a unique combination of practicality and creativity.

The first time I glimpsed Edinburgh Castle, sprouting from the basalt like some giant stone apparition, I was stunned into an uncharacteristic silence. There is something about Edinburgh – indeed about all of Scotland – that inspires not only silence, but also a certain type of creative ingenuity.

You feel this something as soon as you arrive in Scotland’s capital. You feel it in the zigzag of alleyways that is Old Town. You feel it in the raw beauty of Arthur’s Seat, the extinct volcano that towers over the city. You feel it in Edinburgh’s choc-a-block bookshops – living proof of the city’s rich intellectual heritage.

There’s a little bit of Scotland in all of us, whether we know it or not. If you’ve ever consulted a calendar or the Encyclopaedia Britannica, you can thank the Scots. If you’ve ever flushed a toilet or used a refrigerator or ridden a bicycle, thank the Scots.

If you’ve ever had surgery and didn’t feel a thing, you can thank the Scots.

Scottish creativity combines the lofty and the practical. Think of Glasgow’s James Watt and his steam engine, or Fife-born Adam Smith and his classic Wealth of Nations book — or the eagle-eyed detective named Sherlock.

Or, for that matter, a young wizard named Harry.

JK Rowling was a struggling single mother of two, on the dole, when she arrived in Edinburgh in 1993 with her infant daughter in her arms and the first three chapters of Harry Potter and The Sorcerer’s Stonetucked into her suitcase. She wrote the rest in the city’s cafes, including the now-defunct Nicholson’s Café and the very much thriving Elephant House, which sports a sign outside announcing that you’ve arrived at “The Birthplace of Harry Potter”.

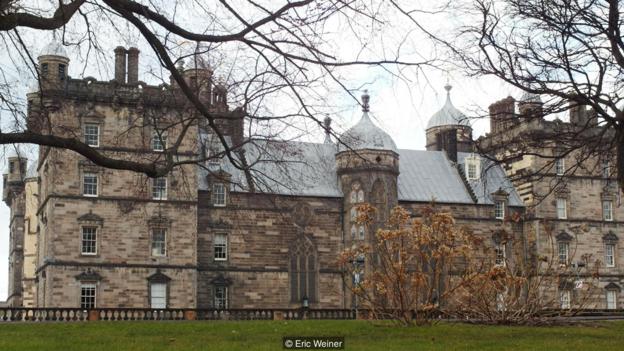

In fact, Edinburgh’s influence on Rowling’s imaginary world of wizardry is unmistakable: as many locals have noted, Hogwarts bears a striking resemblance to George Heriot’s School in Old Town.

In other ways, too, Scotland punches above its creative weight, with writers like Ian Rankin, the popular mystery author, and Alexander McCall Smith, author of the No 1 Ladies Detective Agency series.

Then there is Silicon Glen, Scotland’s high-tech region that is home to some cutting-edge research, such as the real-life “tractor” beams created at the University of Saint Andrews, and the development of a new generation of prosthetics limbs (including some that can be controlled via app) by the Livingston-based firm of Touch Bionics.

But what exactly explains Scottish creativity?

“Edinburgh seems to thrive on surprise,” the playwright Donald Campbell told me over tea at his Edinburgh home. This is true even of the land itself, with its “theatre tricks in the way of scenery”, as Robert Louis Stevenson, an Edinburgh-native, described so wonderfully in his short tome Edinburgh: Picturesque Notes.

It is also true of the people. One day over tea at a café, I sat down with local teacher Muriel Kirton. It was freezing outside, but I spotted a man running by in T-shirt and shorts.

“What’s wrong with him?” I asked.

“He’s Scottish,” she replied, as if that explained everything.

In a way, it does. The Scots are a contradictory people. It was a Scotsman, Adam Smith, who invented the field of economics, and a Scotsman, Thomas Carlyle, who roundly mocked it as “the dismal science”.

“We’re a bit schizophrenic,” conceded Kirton, explaining that, while generally a very cautious person, she once took off for South America on a whim.

The Scots are not only mercurial, they’re also outsiders, perched on the fringe of the United Kingdom. From a creativity perspective, this is good. Throughout history, most creative geniuses have been outsiders in one way or another.

I witnessed Scottish creativity for myself when I visited a local Edinburgh science fair. It was a bit odder than your typical science fair. Exhibits included a polygraph and mouse pads fashioned like oriental carpets, and something called a “solar spectrometer”, which I never figured out what it did. The most popular exhibit was one featuring a 3D printer. That’s where I found Robin Beer. (“Beer, like the drink,” he said with a smile.)

He’s in the software business so, technically, he could live anywhere but, still, there’s something special about Scotland, he said. Yes, this creative spirit is in full bloom each August during the famous Edinburgh Fringe Festival, the world’s largest arts festival, but, according to Beer, Scottish ingenuity is a year-round affair. In fact, he said, he finds the long Scottish winter to be the most inspiring time. “The darkness and cold forces you to stay indoors and get creative.”

I was sceptical. Never mind penning a great work of literature or inventing a world-changing contraption, I was finding it hard to get out of bed. At this latitude, late winter mornings are not your friend; the darkness and the chill conspired with my down comforter to immobilize me. I might easily have slept until noon, were it not for the words of Robert Louis Stevenson, mocking me, cajoling me out from under the covers. “The great affair is to move,” he said.

So I moved. First to the shower, then to breakfast, then, boldly, in the spirit of adventurers through the ages, outside. I joined a walking path along Edinburgh’s main canal. I was not alone. Others were heeding Stevenson’s advice; they were walking and running and cycling, and doing so in attire – T-shirts and shorts – that, to my non-Scottish mind, seemed wholly inappropriate given the biting cold.

The word scrappy sprung to mind. Yes, that is what the Scots are. They are scrappy. I had not previously associated the word with creative genius, but perhaps I should. As I picked up my pace in a futile attempt to stave off hypothermia, it dawned on me how that word, scrappy, explains much of Scotland’s creative spark.

Scrappy, I decide, deserves a better connotation. Scrappy is not mere pluck or stubborn persistence. Scrappy people are resourceful, determined and grudgingly optimistic. Scrappy is good. It is also very Scottish.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом