Never drink whisky on the rocks

The Thirsty Explorer heads to the Scottish island of Islay where he learns the important differences between malt and whisky – and how to order it in a bar.

The first time I tasted Scotch whisky I was a broke student, chugging direct from a £3 bottle, lying outside my tent at the foot of Ben Nevis, Britain’s highest mountain. It was after a meal of tinned macaroni and cheese – hardly a sophisticated sampling considering I was sipping the world’s most venerated style of whisky. I promised myself that the next time I returned to Scotland, I would drink the best the country had to offer, in great abundance and straight from the source, no matter what it took.

It turns out, for me, all it took was a smile and a stiff right thumb.

That first Scotch whisky I drank was a blend. Of course, I didn’t understand the difference between single malt and blended whisky until I returned to Scotland eight years later; most people still don’t. Blended whisky, which comprises more than 80% of the market, including brands like Johnnie Walker and Dewars, is a mix of malt and grain whiskies that come from multiple distilleries. Single malt, which Scottish drinkers often refer to as malt rather than whisky (and never Scotch, like it’s known elsewhere around the world), is whisky created from malted barley at one distillery.

Single malts aren’t necessarily always better than blends, but most of Scotland’s highest regarded and most expensive whiskies are the former. Blended whiskies are smoother and easier to drink; malt can be almost overwhelming in flavour, a drink most work their way up to.

The vast majority of malt comes from three major whisky-producing regions. The Highlands (roughly the northern half of Scotland) and Speyside (in the country’s northeast) are both easily accessible from major cities, and their whiskies are relatively accessible to the malt novice, characterised by smooth, floral, often delicate flavours.

Then there’s Islay, the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides, about 32km off the coast of Northern Ireland. As the crow flies, it’s a roughly 113km journey from Glasgow to Islay. But, unless you plan on flying into the island’s tiny airport, it’s about 2.5 hours by car from Glasgow to the hamlet of Kennacraig, and a nearly three-hour ferry to Islay – and that’s if you time the trip perfectly. Many people find Islay’s whisky even less accessible than the island itself.

If you’re a seasoned malt drinker, chances are you have a bottle from Islay in your liquor cabinet. If, on the other hand, you tried Scotch whisky for the first time and hated it, thought it was too smoky, or tasted like medicine or ashtrays, it probably came from Islay.

Islay whiskies get their signature flavour from smoking peat – the same vegetation that Scots have long been burning to heat their homes – in order to dry the malted barley used to create whisky. The results are polarising; some purists believe the peat takes away from the true flavour of the whisky, others become addicted, perpetually searching for something peatier.

The amount of peat used varies widely. Bruichladdich is the only Islay distillery known for its non-smoked whiskies. Laphroaig, on the other end of the island and the other end of the peat spectrum, unapologetically overwhelms the palate with peat.

Laphroaig’s recent “Opinions Welcome” campaign received feedback that varied from “like chewing on a well-tarred fishing boat” to “drinking the inside of an antique store”. The opinion that resonated most with me reads, “It’s like fighting a peat bog monster that is on fire, but suddenly you both pause, look in one another’s eyes and kiss.”

Wine drinkers like to talk about terroir: the environmental condition, geology and geography that give a wine (and the grapes that make it) its unique flavour. However, it takes a connoisseur of snobbish proportions to know a wine’s exact origin from a blind taste. Even an amateur drinker would probably know in one sip whether a whisky came from Islay.

I’ve never tasted another drink that has more successfully bottled a place. The whisky truly tastes like Islay, distilled – of the peat bogs that cover the island, of the smoke and fire used to stay warm during a seemingly endless winter, of the salty aftertaste of the sea.

Nothing about Islay is easy. The island is rugged and tempestuous; winds gusting straight from the sea are powerful and unrelenting. Clusters of white-washed buildings make up the two main villages of Bowmore and Port Ellen; the rest of the island is mostly inhabited by sheep and birds, and largely covered in peat. The peat bogs, which take thousands of years to form and require a perfect storm of climatic conditions, spread across the island for miles.

Public transportation on the 25-mile-long island is a nightmare, and driving and visiting distilleries don’t really mix. So for three days on Islay, I held out my thumb and was whisked away by kindly locals, travelling from the windswept shores to the warm and welcoming shelters of the island’s eight distilleries, sampling dozens of whiskies in all their smoky glory.

For me, distilleries are near magical places, where alchemy meets science to create something far greater than the sum of its parts. They are also museums of smells, where each room has a beautiful and distinct scent.

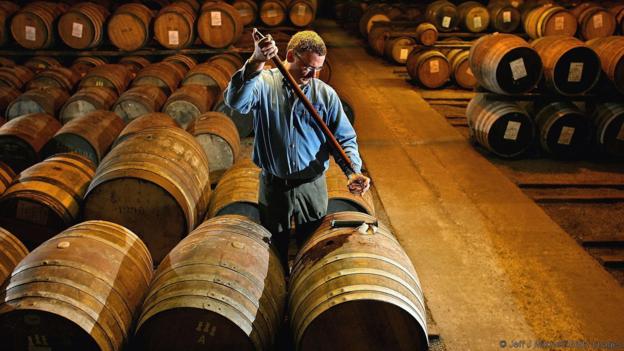

Visiting Scottish distilleries is also an incredible deal. Between £5 and £7 generally gets you a tour of the facility and a dram (a small glass) or two of cask-strength whisky (whisky before water is added). Many distilleries also offer pricier warehouse tastings (upwards of £25 each), giving the chance to sample rare whiskies straight from the barrel, including some whiskies that are impossible to find anywhere else and others that you may never taste again.

My favourite Islay warehouse tasting was at Lagavulin, where £12 (combined with the Friends of the Classic Malts free admission) got me a sample of an eight-year old whisky still too young for bottling (the unpleasant flavour highlighted how important those years in the barrel are). I also got to try a double-matured bottle (aged 16 years in bourbon barrels before being finished for a few months in sherry casks) and a 30-year malt that normally costs more than £50 a dram in a bar, if you can find it (most single malts are aged at least 10 years, and generally get more expensive with age).

Speaking of bars, there is a certain protocol to ordering malt in Scotland. First, please don’t call it Scotch. It’s whisky or malt. Second, unless you want to be the subject of ridicule, don’t order your malt on the rocks. Ice numbs the tongue and melts too fast. You either drink it neat or with a drop of water to open the flavours. Drinking it on the rocks is only acceptable if you’re drinking a blended whisky or if it’s scorching outside. But the odds of the latter happening are incredibly slim. In Scotland, summer is the second most famous myth after the Loch Ness Monster.

After having been to Islay – even during Brooklyn’s oppressive summer heat – I still order my malt neat. I carefully pore over the bar’s menu, having forgotten more about whisky than most people will ever know. And even if it’s eight months (or more) until I find myself in Scotland again, I know it will only take one sip of that 16-year Lagavulin to transport me back to Islay’s windy, mountainous, peat-covered shores.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом