She satirised the 60s alongside Peter Cook and appeared onscreen in classics from Alfie to Women in Love. Bron talks Corbyn, ‘consorts’, and what the Beatles taught her about fame

Eleanor Bron – delicate, poised and with fathomless, deep-hooded eyes – has had a long career. It stretches back to the satire boom of the 1960s, through a constellation of films such as Ken Russell’s Women in Love and Terence Davies’s The House of Mirth and up to this month, in rehearsals for a play at the Bush theatre in London. But the absolute keynote of performing, she says, is still “dread”. Acting “is terribly exposing”. The fear doesn’t wear off with experience? “It gets worse as one gets older. You have what I call peripherals – some of the constant peripherals are the dread, the fear, the constant possibility of failure. Of letting other people down, that is the main thing. But nowadays everything has changed in terms of scale. Everything has become more pressured, more PR.”

She makes an elegant gesture with her hand that indicates the space of our conversation, which is taking place in the corner of a rehearsal room. The appetite for “presentation and dazzle” tends towards the hyper-commodification of the culture, she argues. (She has just been on a run of reading Naomi Klein’s books about capitalism.) Acting, writing and other creative acts are reduced to formulas that can be taught, and thus packaged and sold. “Casting, I’ve heard, may depend on how many people follow you on Twitter. It’s the world as it is, but it’s not the world that I am comfortable in any longer.” She rejoined the Labour party to vote for Jeremy Corbyn.

The play she is preparing, however, is “beautifully written and he doesn’t do dazzle: it’s very wrought, but it goes to the core of something,” she says. The work is Tom Holloway’s Forget Me Not (2011), about the policy, between 1945 and 1968, of sending deprived, illegitimate or orphaned British children to Australian institutions, where they often suffered great hardship and abuse. Bron plays a mother, Mary, whose son Gerry journeys back to Liverpool to find her. When Steven Atkinson, artistic director of the theatre company HighTide, asked Bron to consider the part she was fascinated, since a working-class Liverpudlian is “absolutely not the part that many people would think of for me. I usually – well I used to, though now my hair’s white it’s not quite so compelling – get cast as either exotic, sort of foreign, or, curiously, upper-class, which is no part of my makeup.”

Bron was born in Stanmore, Middlesex, in 1938. Her father, who had changed his name from Bronstein, owned a music publishing company. They were a moderately observant Jewish family; Bron herself is “full of horror at what religion does to women” – and gave a talk at a reform synagogue recently that she’d been tempted to call Man’s Inhumanity to Woman. At school, she’d announced her intention to apply to drama school to her headmistress – who said: “‘Oh, all little girls want to go to drama school,’ and I immediately thought, ‘I don’t want to be like all little girls.’ She urged me to go to Oxford or Cambridge. That generation of [women] teachers had all been deprived of their dues academically – the possibility of a really good university education – so they wanted it for other people.”

I used to get cast as either exotic or upper class, which is not part of my makeup.

At Cambridge, where she studied French and German, she was, she says, “spotted” by fellow student John Bird, the writer and satirist. She is convinced she would never have become an actor if she had been to drama school (“I think I would have found it terribly oppressive and very frightening”) and indeed, took a job in the personnel department of De La Rue, the company that prints banknotes, after she graduated. But it was unbearably boring (“I had a day-release course in statistics: I think that’s what did it”). She joined the Establishment – a satirical cabaret set up by Peter Cook. They did the pilot for That Was the Week That Was, the pioneering, hugely influential but short-lived BBC television satire show directed by Ned Sherrin. But then they took the Establishment to Chicago and New York, and so a different cast took on TW3. Later, she was on TV three nights a week with the programme’s successor, Not So Much a Programme, More a Way of Life.

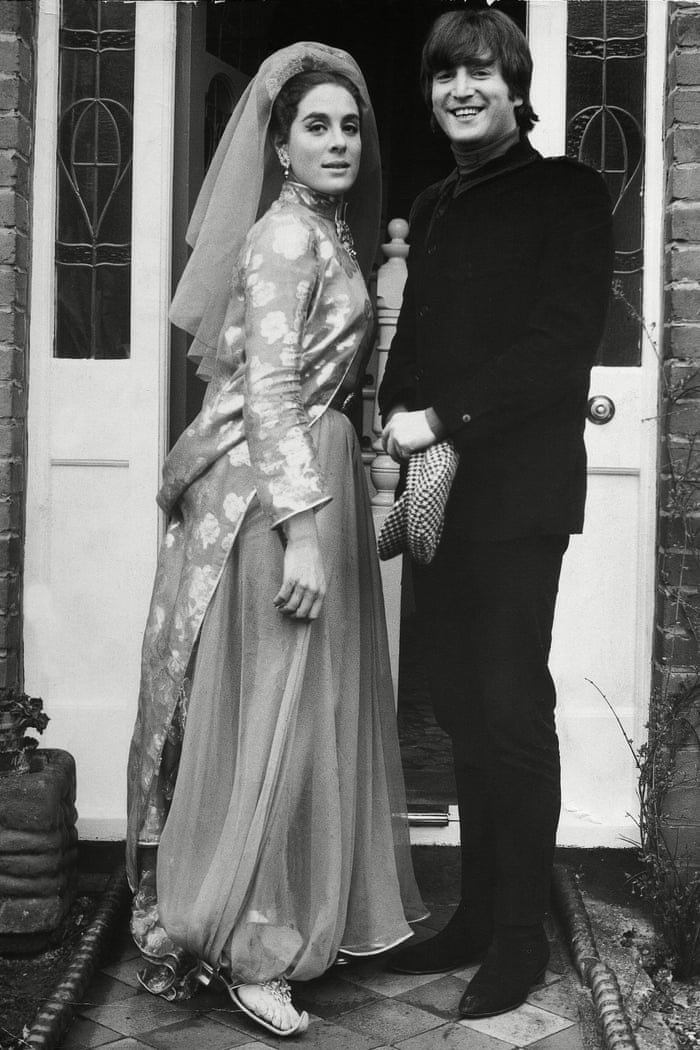

There was more to life than satire, though: Bron worked in rep in Bristol, played the Duchess of Malfi at the National and was cast in movies – aside from Women in Love there were roles in The National Service and Alfie and Help!, the Beatles’ 1965 film. The last, she says, “taught me that fame is not all it’s cracked up to be. It is going back to the Greeks: it is Orpheus and his tearing apart by the Maenads … you set up these demigods, and they are torn apart.” She was dazzlingly beautiful in those days – as she continues to be, with her glorious white curls and enormous elegance. There has also, always, been writing – a novel, a couple of autobiographical books, such as The Pillow Book of Eleanor Bron, that in fact did very well at protecting her own privacy, indiscriminately referring to all her lovers as “John”. She kept her long-term relationship with the visionary architect Cedric Price, who died in 2003, very much to herself for decades. She likes to use the word “consort” to describe him, “which sounds as if you have fun together. Not partner – he didn’t use any of those words.”

These days, she’s been – much to the delight of its fans – in The Archers, playing Carol Tregorran, Jill Archer’s old pal. She’s not entirely sure if she’ll be reappearing – “I haven’t been in for a while, and they’ll call me when they need me.” She herself loves the show. “I think it’s a sort of virtual Moral Maze, except much better because it puts people right into a moral situation and asks them to make judgments about behaviour. At the moment, it is raising some quite difficult problems. Such as men bullying women – isn’t it amazing how it’s grabbed everyone?” She is referring to the most gripping storyline of the moment, Rob Titchener’s fiendish controlling of his wife, Helen Archer.

More than ever, she’s been writing. At the moment, she is working on a series of plays (she calls them “divagations”) in rhyming couplets (very unfashionable, she says, although with Mike Bartlett’s Charles III storming Broadway in blank verse, perhaps very much the thing). One of them is set in Delphi and the six characters are the Pythias, the priestesses through whom the god Apollo supposedly sent his oracular pronouncements. According to one historical account, after a Pythia was raped in the third century BC, only women over 50 were appointed to the role, and so the play addresses a lack of parts for older women. She’s not done too much about getting the plays performed, although there have been successful readings. The joy is in the writing: “I’d rather be doing it than pushing it, actually.” She adds, with a cheerful glint, “which could be also said of drugs, come to think of it”.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом