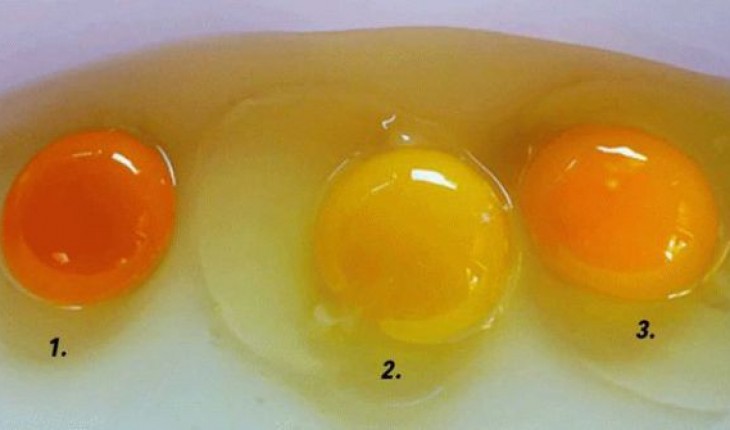

Can You Guess Which Of These Egg Yolks Is Actually From A HEALTHY Chicken?

Chicken eggs vary in size and color of the shell but if an egg comes from the family farm, the yolk is almost always a darker color. It is also thicker than the typical yellow yolk you find at the store. One of the more interesting aspects of living in Brazil is the different approaches to food. We are connected to local farms from friends and family, spoiling us with organic homegrown everything.

In the United States all the eggs that can be bought at our local supermarket are yellow. Organic, vegetarian or cheap; they are all yellow and the yolk is not as thick.

What is the reason for this? Could it be that myself and almost everyone I know has been eating eggs from unhealthy chickens? Have you ever even seen an orange egg? It took me 30 years to discover an egg from a healthy chicken. That's crazy.

Having returned to the states, Craigslist is the go-to route to accommodate my urban life with homestead flare in search of the dankest foods. From Garden Betty: Last year, I compared my pasture-foraging, insect-pecking, soil-scratching, whole grain-feeding chickens' yolks to the yolks of both their “free-ranging” and factory-farmed counterparts.

They are clearly visible: Yolks from my homegrown eggs were not only darker orange, but also fuller and thicker. Even the eggshells were denser and harder to crack. But what's the big deal about orange yolks? Besides being a coveted color, orange yolks are an indication of a well balanced and highly nutritious diet.

A few things factor into the making of an orange yolk: xanthophylls, omega-3 fatty acids, and meats. Xanthophylls are a class of carotenoids. Carotenoids are natural plant pigments found in many fruits and vegetables.

It's often thought that beta-carotene, one of the more well-known carotenoids, is responsible for giving yolks the orange pigment that people associate with carrots. But in actuality, beta-carotene benefits yolks nutritionally, rather than colorfully. The carotenoids that cause deeper yolk coloring are xanthophylls, which are more readily absorbed in the yolks.

(Lutein is one such xanthophyll, and a lot of lutein means a lot more orange.) Xanthophylls are found in dark leafy greens like spinach, kale and collards, as well as in zucchini, broccoli, and brussels sprouts. Omega-3 fatty acids are highly concentrated in flax seeds and sea kelp, which are both important components of my homemade whole grain chicken feed.

And did you know that chickens are not meant to be vegetarian, no matter what your premium carton of organic/grain-fed/cage-free eggs tells you? Chickens are omnivores by nature and their healthiest diets include meats, such as mealworms, beetles, grasshoppers, grubs, and whatever creepy-crawly they can pull out of the ground. I've even heard of chickens (those ballsy ones out in the boonies) attacking small rodents and snakes!

When you have all of these sources incorporated into a hen's healthful diet, the nutrients they consume are passed on to their eggs and concentrated in their yolks. According to Mother Earth News, which conducted its own egg analysis, and a more recent Pennsylvania State University study, pastured eggs contain higher levels of vitamins A, D and E; more beta-carotene; and more omega-3s.

All this means is that a pastured egg is better for you. And that's one of the reasons we raise chickens, right? So, how do we get those delightful dark orange yolks from our backyard chickens?

Let your ladies roam a pasture (or a garden — especially if you're digging over new beds — or even just a new patch of dirt in their chicken tractor) for an orange-boosting bug buffet.

Give them plenty of fresh greens to increase the lutein in their yolks. The darker the green the better, so I often fix them a feast of edible amaranth (one of my favorite summer greens), kale, collards, broccoli leaves, or whatever I happen to have growing in my garden. If it's the middle of winter and your garden greens are lacking, you can feed them alfalfa.

They're very handy helpers at the end of the season when most of my greens have bolted and become bug-ridden. Let the chickens clean up those plants before you pull them out for your compost pile. It's a win for everybody! (Except the bugs, that is…).

(As an aside, don't be fooled by the cheater method that egg factories take, and simply feed your chickens more corn. While corn can give your yolks that nice golden color, it has little nutritional value.)

After a few weeks, you'll be so used to seeing orange yolks (the way most of us have been conditioned to see yellow yolks) that you might even think they haven't changed in color. Buy some eggs from the store and crack them into a bowl with your homegrown eggs — you'll be stunned at the difference!

Those are some interesting observations by Garden Betty. Here is a bit more of an explanation by food and nutrition.

When it comes to yolks, the color is determined by a hen's diet, not its breed (artificial color additives are not permitted in eggs) or the freshness of the egg. Hen diets heavy in green plants, yellow corn, alfalfa and other plant material with xanthophylls pigment (a yellow-orange hue) will produce a darker yellow-orange yolk. Diets of wheat or barley produce pale yellow yolks; hens fed white cornmeal produce almost colorless yolks.

Free-range hens may have access to more heavily pigmented food so they may produce eggs with darker yolks. According to the American Egg Board, consumer preference in the U.S. is typically for light gold- or lemon-colored yolks.

At the end of the day, know your farmer and the diet of the chickens producing the eggs to be eaten.

Политика конфиденциальности | Правила пользования сайтом